Survey of 2,778 AI authors: six parts in pictures

Crossposted from AI Impacts blog

The 2023 Expert Survey on Progress in AI is out, this time with 2778 participants from six top AI venues (up from about 700 and two in the 2022 ESPAI), making it probably the biggest ever survey of AI researchers.

People answered in October, an eventful fourteen months after the 2022 survey, which had mostly identical questions for comparison.

Here is the preprint. And here are six interesting bits in pictures (with figure numbers matching paper, for ease of learning more):

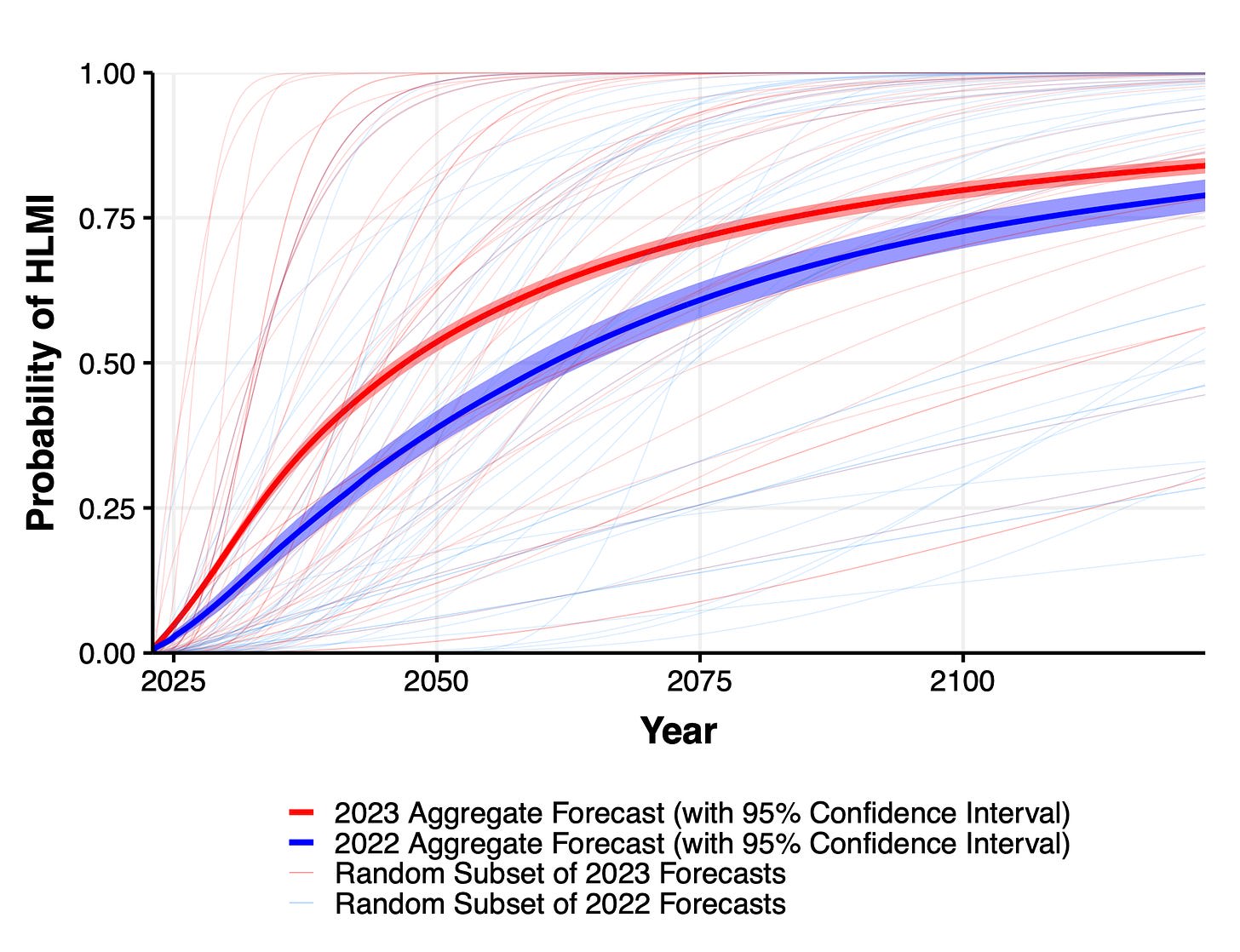

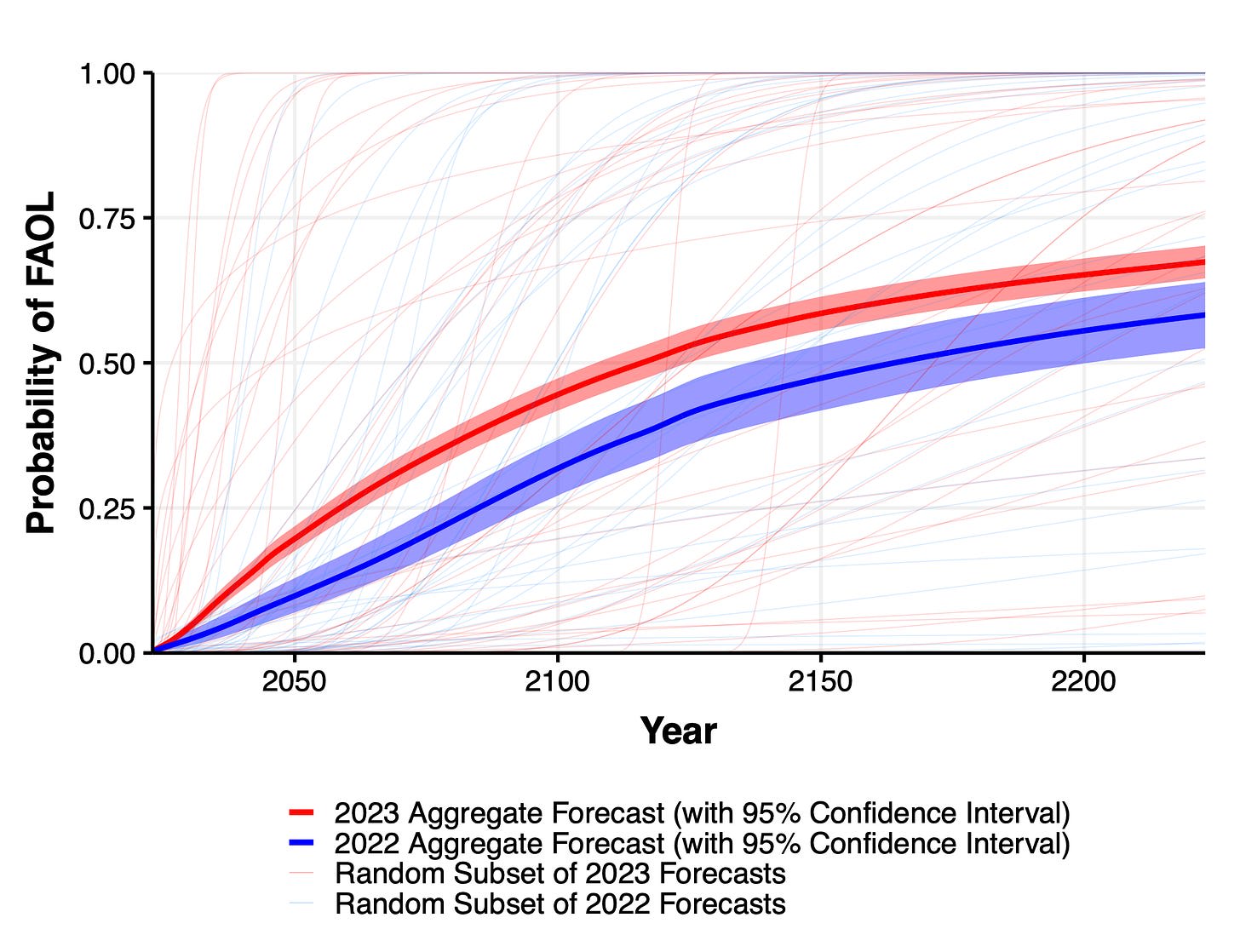

1. Expected time to human-level performance dropped 1-5 decades since the 2022 survey. As always, our questions about ‘high level machine intelligence’ (HLMI) and ‘full automation of labor’ (FAOL) got very different answers, and individuals disagreed a lot (shown as thin lines below), but the aggregate forecasts for both sets of questions dropped sharply. For context, between 2016 and 2022 surveys, the forecast for HLMI had only shifted about a year.

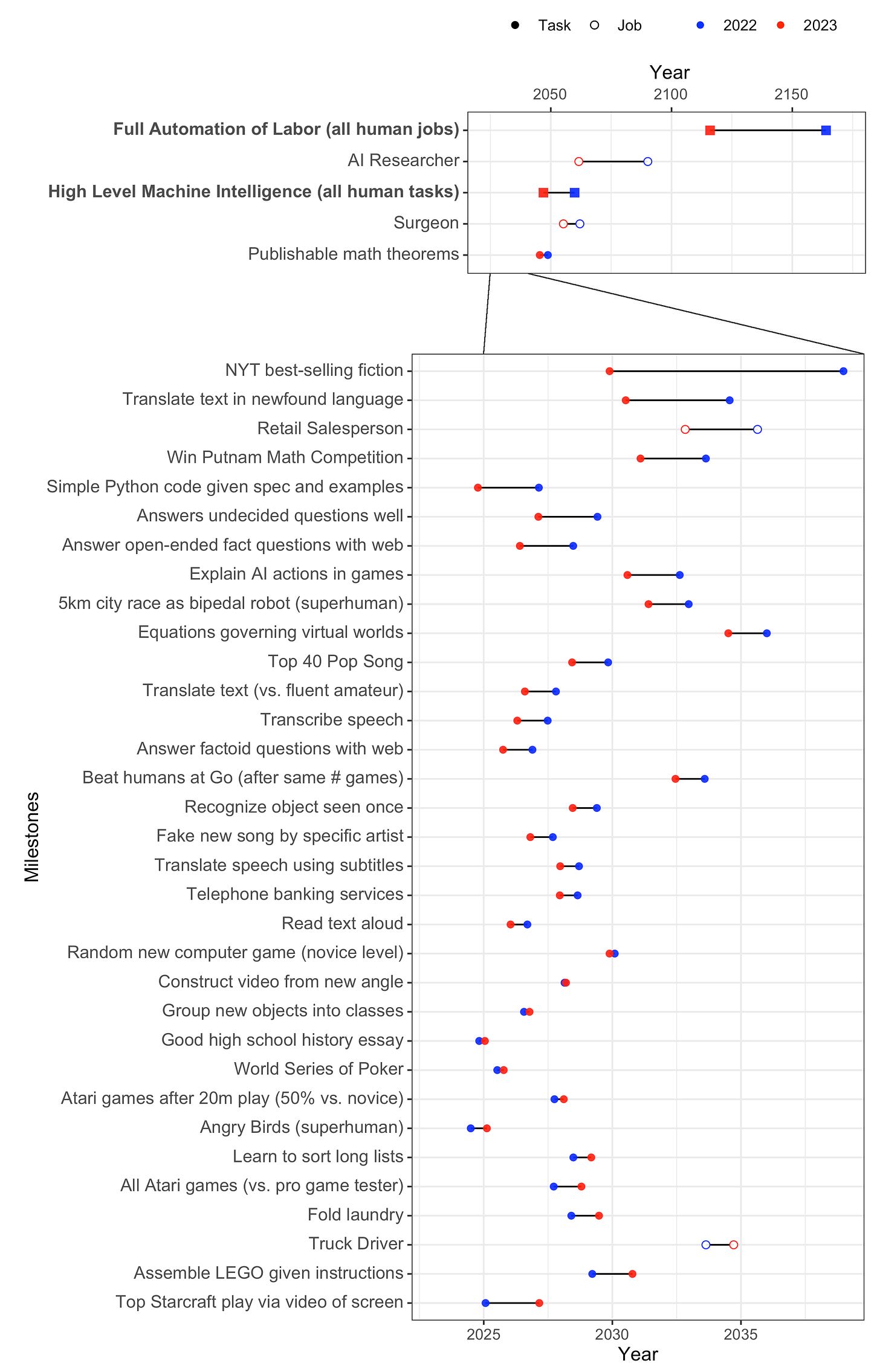

2. Time to most narrow milestones decreased, some by a lot. AI researchers are expected to be professionally fully automatable a quarter of a century earlier than in 2022, and NYT bestselling fiction dropped by more than half to ~2030. Within five years, AI systems are forecast to be feasible that can fully make a payment processing site from scratch, or entirely generate a new song that sounds like it’s by e.g. Taylor Swift, or autonomously download and fine-tune a large language model.

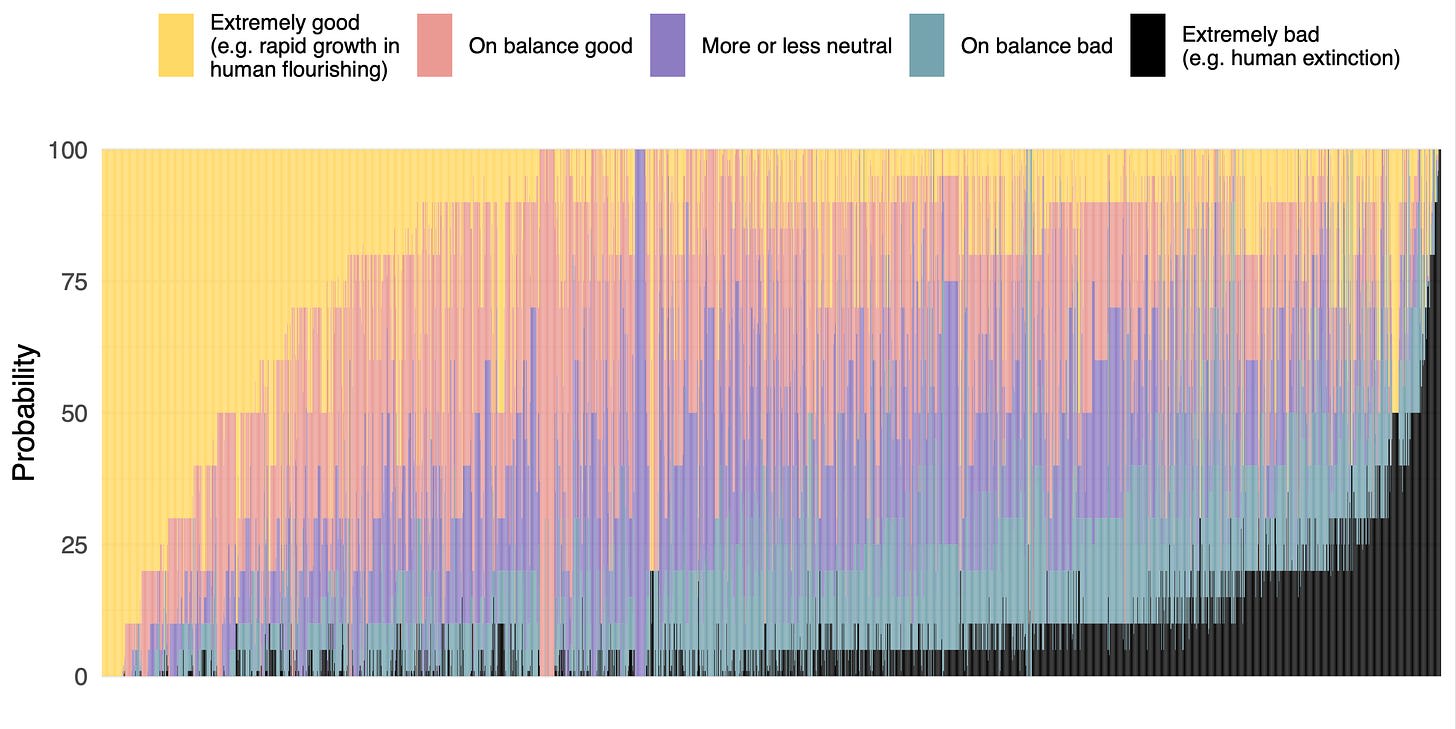

3. Median respondents put 5% or more on advanced AI leading to human extinction or similar, and a third to a half of participants gave 10% or more. This was across four questions, one about overall value of the future and three more directly about extinction.

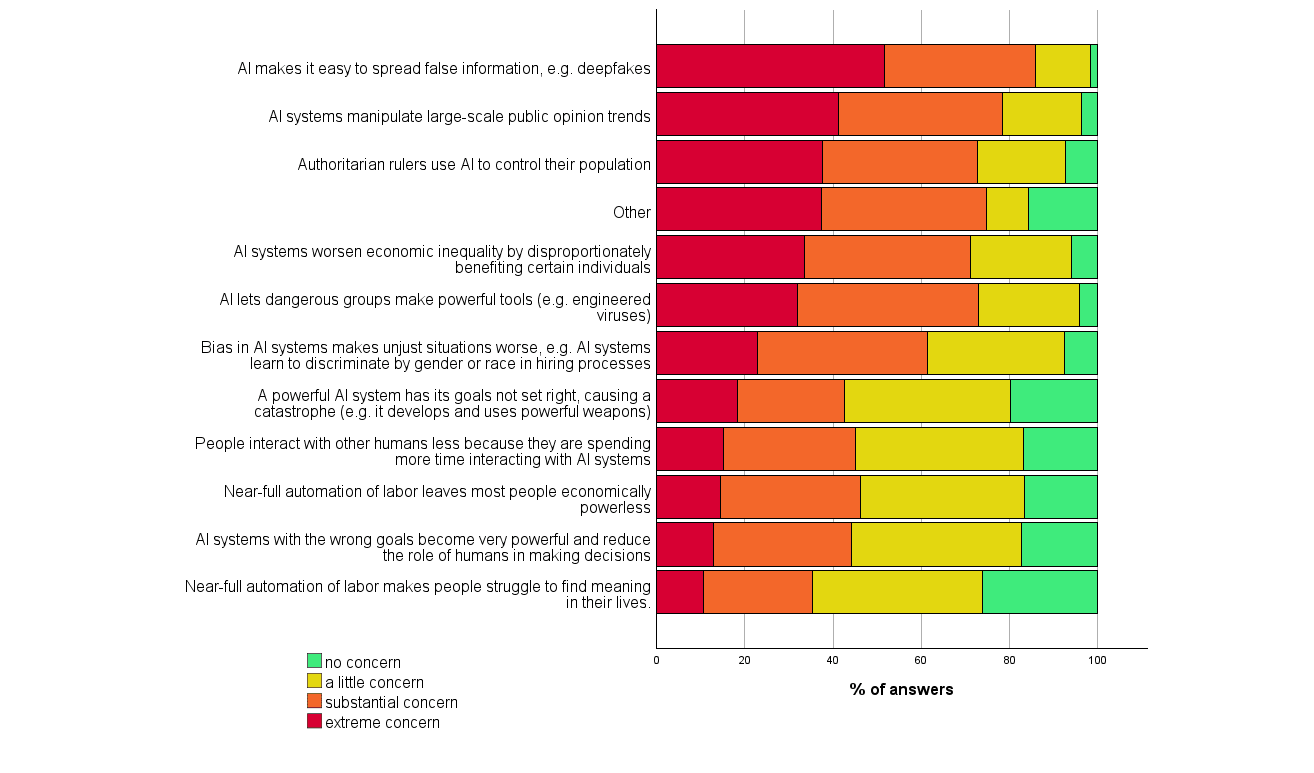

4. Many participants found many scenarios worthy of substantial concern over the next 30 years. For every one of eleven scenarios and ‘other’ that we asked about, at least a third of participants considered it deserving of substantial or extreme concern.

5. There are few confident optimists or pessimists about advanced AI: high hopes and dire concerns are usually found together. 68% of participants who thought HLMI was more likely to lead to good outcomes than bad, but nearly half of these people put at least 5% on extremely bad outcomes such as human extinction, and 59% of net pessimists gave 5% or more to extremely good outcomes.

6. 70% of participants would like to see research aimed at minimizing risks of AI systems be prioritized more highly. This is much like 2022, and in both years a third of participants asked for “much more”—more than doubling since 2016.

If you enjoyed this, the paper covers many other questions, as well as more details on the above. What makes AI progress go? Has it sped up? Would it be better if it were slower or faster? What will AI systems be like in 2043? Will we be able to know the reasons for its choices before then? Do people from academia and industry have different views? Are concerns about AI due to misunderstandings of AI research? Do people who completed undergraduate study in Asia put higher chances on extinction from AI than those who studied in America? Is the ‘alignment problem’ worth working on?