-

Podcast: Eye4AI on 2023 Survey

I talked to Tim Elsom of Eye4AI about the 2023 Expert Survey on Progress in AI (paper):

-

Movie posters

Life involves anticipations. Hopes, dreads, lookings forward.

Looking forward and hoping seem pretty nice, but people are often wary of them, because hoping and then having your hopes fold can be miserable to the point of offsetting the original hope’s sweetness.

Even with very minor hopes: he who has harbored an inchoate desire to eat ice cream all day, coming home to find no ice cream in the freezer, may be more miffed than he who never tasted such hopes.

And this problem is made worse by that old fact that reality is just never like how you imagined it. If you fantasize, you can safely bet that whatever the future is is not your fantasy.

I have never suffered from any of this enough to put me off hoping and dreaming one noticable iota, but the gap between high hopes and reality can still hurt.

I sometimes like to think about these valenced imaginings of the future in a different way from that which comes naturally. I think of them as ‘movie posters’.

When you look fondly on a possible future thing, you have an image of it in your mind, and you like the image.

The image isn’t the real thing. It’s its own thing. It’s like a movie poster for the real thing.

Continue reading → -

Are we so good to simulate?

If you believe that,—

a) a civilization like ours is likely to survive into technological incredibleness, and

b) a technologically incredible civilization is very likely to create ‘ancestor simulations’,

—then the Simulation Argument says you should expect that you are currently in such an ancestor simulation, rather than in the genuine historical civilization that later gives rise to an abundance of future people.

Not officially included in the argument I think, but commonly believed: both a) and b) seem pretty likely, ergo we should conclude we are in a simulation.

I don’t know about this. Here’s my counterargument:

- ‘Simulations’ here are people who are intentionally misled about their whereabouts in the universe. For the sake of argument, let’s use the term ‘simulation’ for all such people, including e.g. biological people who have been grown in Truman-show-esque situations.

- In the long run, the cost of running a simulation of a confused mind is probably similar to that of running a non-confused mind.

- Probably much, much less than 50% of the resources allocated to computing minds in the long run will be allocated to confused minds, because non-confused minds are generally more useful than confused minds. There are some uses for confused minds, but quite a lot of uses for non-confused minds. (This is debatable.) Of resources directed toward minds in the future, I’d guess less than a thousandth is directed toward confused minds.

- Thus on average, for a given apparent location in the universe, the majority of minds thinking they are in that location are correct. (I guess at at least a thousand to one.)

- For people in our situation to be majority simulations, this would have to be a vastly more simulated location than average, like >1000x

- I agree there’s some merit to simulating ancestors, but 1000x more simulated than average is a lot - is it clear that we are that radically desirable a people to simulate? Perhaps, but also we haven’t thought much about the other people to simulate, or what will go in in the rest of the universe. Possibly we are radically over-salient to us. It’s true that we are a very few people in the history of what might be a very large set of people, at perhaps a causally relevant point. But is it clear that is a very, very strong reason to simulate some people in detail? It feels like it might be salient because it is what makes us stand out, and someone who has the most energy-efficient brain in the Milky Way would think that was the obviously especially strong reason to simulate a mind, etc.

-

Shaming with and without naming

Suppose someone wrongs you and you want to emphatically mar their reputation, but only insofar as doing so is conducive to the best utilitarian outcomes. I was thinking about this one time and it occurred to me that there are at least two fairly different routes to positive utilitarian outcomes from publicly shaming people for apparent wrongdoings*:

A) People fear such shaming and avoid activities that may bring it about (possibly including the original perpetrator)

B) People internalize your values and actually agree more that the sin is bad, and then do it less

Continue reading → -

Parasocial relationship logic

If:

-

You become like the five people you spend the most time with (or something remotely like that)

-

The people who are most extremal in good ways tend to be highly successful

Should you try to have 2-3 of your five relationships be parasocial ones with people too successful to be your friend individually?

Continue reading → -

-

Deep and obvious points in the gap between your thoughts and your pictures of thought

Some ideas feel either deep or extremely obvious. You’ve heard some trite truism your whole life, then one day an epiphany lands and you try to save it with words, and you realize the description is that truism. And then you go out and try to tell others what you saw, and you can’t reach past their bored nodding. Or even you yourself, looking back, wonder why you wrote such tired drivel with such excitement.

Continue reading → -

Survey of 2,778 AI authors: six parts in pictures

Crossposted from AI Impacts blog

The 2023 Expert Survey on Progress in AI is out, this time with 2778 participants from six top AI venues (up from about 700 and two in the 2022 ESPAI), making it probably the biggest ever survey of AI researchers.

People answered in October, an eventful fourteen months after the 2022 survey, which had mostly identical questions for comparison.

Here is the preprint. And here are six interesting bits in pictures (with figure numbers matching paper, for ease of learning more):

1. Expected time to human-level performance dropped 1-5 decades since the 2022 survey. As always, our questions about ‘high level machine intelligence’ (HLMI) and ‘full automation of labor’ (FAOL) got very different answers, and individuals disagreed a lot (shown as thin lines below), but the aggregate forecasts for both sets of questions dropped sharply. For context, between 2016 and 2022 surveys, the forecast for HLMI had only shifted about a year.

Continue reading →(Fig 3)

(Fig 4)

-

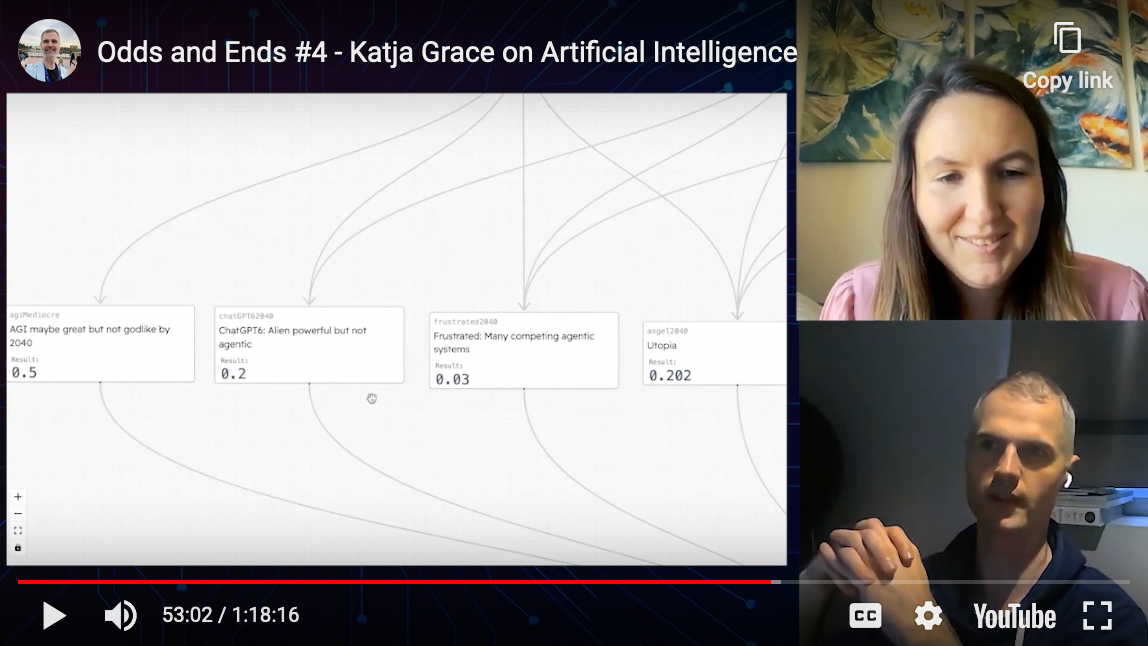

I put odds on ends with Nathan Young

I forgot to post this in August when we did it, so one might hope it would be out of date now but luckily/sadly my understanding of things is sufficiently coarse-grained that it probably isn’t much. Though all this policy and global coordination stuff of late sounds promising.

-

A to Z of things

I wanted to give my good friends’ baby a book, in honor of her existence. And I recalled children’s books being an exciting genre. Yet checking in on that thirty years later, Amazon had none I could super get behind. They did have books I used to like, but for reasons now lost. And I wonder if as a child I just had no taste because I just didn’t know how good things could be.

What would a good children’s book be like?

When I was about sixteen, I thought one reasonable thing to have learned when I was about two would have been the concepts of ‘positive feedback loop’ and ‘negative feedback loop’, then being taught in my year 11 class. Very interesting, very bleedingly obvious once you saw it. Why not hear about this as soon as one is coherent? Evolution, if I recall, seemed similar.

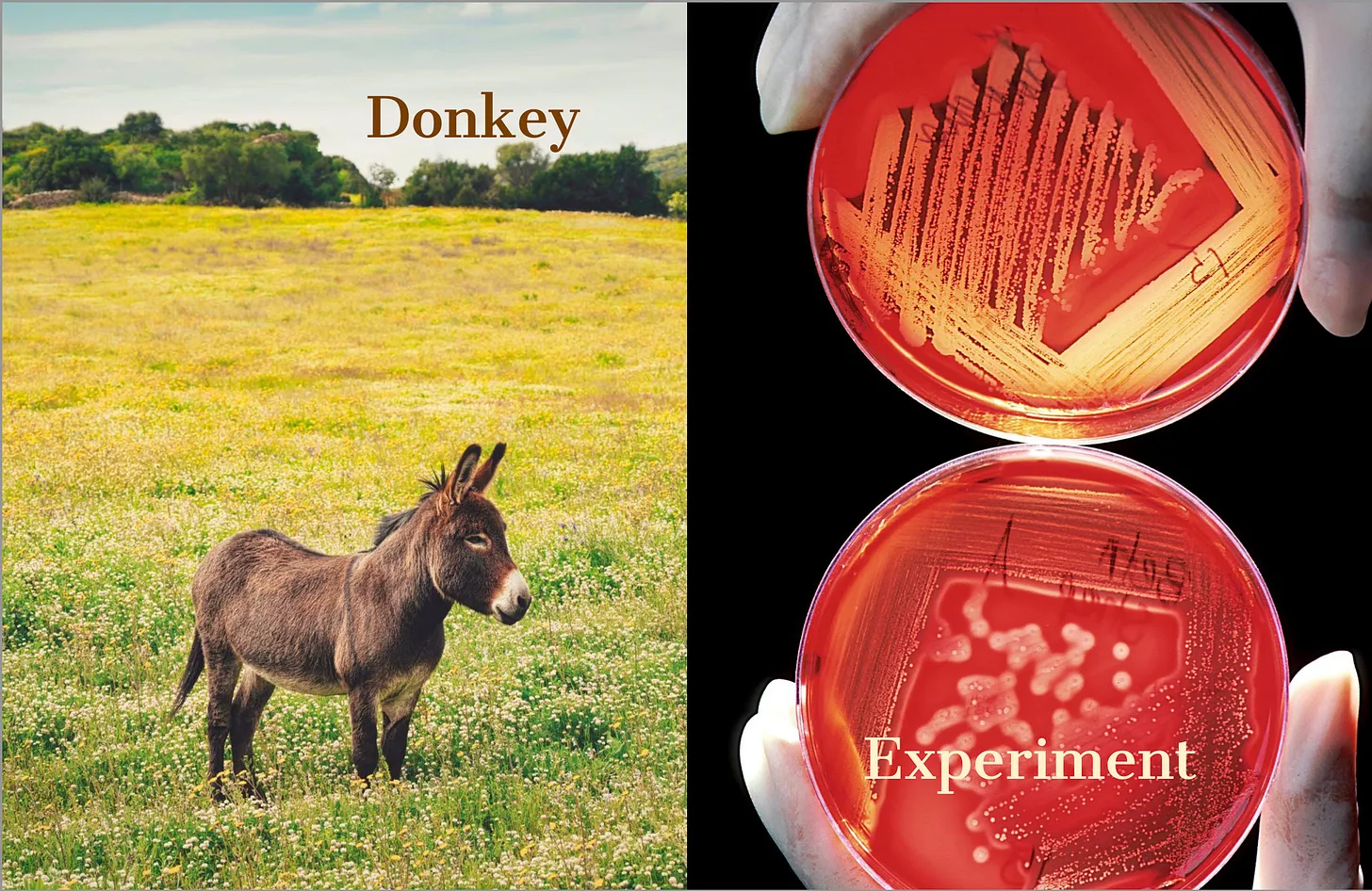

Here I finally enact my teenage self’s vision, and present A to Z of things, including some very interesting things that you might want a beautiful illustrative prompt to explain to your child as soon as they show glimmerings of conceptual thought: levers, markets, experiments, Greece, computer hardware, reference classes, feedback loops, (trees).

I think so far, the initial recipient is most fond of the donkey, in fascinating support of everyone else’s theories about what children are actually into. (Don’t get me wrong, I also like donkeys—when I have a second monitor, I just use it to stream donkey cams.) But perhaps one day donkeys will be a gateway drug to monkeys, and monkeys to moths, and moths will be resting on perfecttly moth-colored trees, and BAM! Childhood improved.

Anyway, if you want a copy, it’s now available in an ‘email it to a copy shop and get it printed yourself’ format! See below. Remember to ask for card that is stronger than your child’s bite.

[Front]

[Content]

-

The other side of the tidal wave

I guess there’s maybe a 10-20% chance of AI causing human extinction in the coming decades, but I feel more distressed about it than even that suggests—I think because in the case where it doesn’t cause human extinction, I find it hard to imagine life not going kind of off the rails. So many things I like about the world seem likely to be over or badly disrupted with superhuman AI (writing, explaining things to people, friendships where you can be of any use to one another, taking pride in skills, thinking, learning, figuring out how to achieve things, making things, easy tracking of what is and isn’t conscious), and I don’t trust that the replacements will be actually good, or good for us, or that anything will be reversible.

Even if we don’t die, it still feels like everything is coming to an end.

EVERYTHING — WORLDLY POSITIONS — METEUPHORIC