Do incoherent entities have stronger reason to become more coherent than less?

My understanding is that various ‘coherence arguments’ exist, of the form:

- If your preferences diverged from being representable by a utility function in some way, then you would do strictly worse in some way than by having some kind of preferences that were representable by a utility function. For instance, you will lose money, for nothing.

- You have good reason not to do that / don’t do that / you should predict that reasonable creatures will stop doing that if they notice that they are doing it.

For example, from Arbital:

Well, but suppose I declare to you that I simultaneously:

- Prefer onions to pineapple on my pizza.

- Prefer pineapple to mushrooms on my pizza.

- Prefer mushrooms to onions on my pizza.

…

Suppose I tell you that I prefer pineapple to mushrooms on my pizza. Suppose you’re about to give me a slice of mushroom pizza; but by paying one penny ($0.01) I can instead get a slice of pineapple pizza (which is just as fresh from the oven). It seems realistic to say that most people with a pineapple pizza preference would probably pay the penny, if they happened to have a penny in their pocket.[1]

After I pay the penny, though, and just before I’m about to get the pineapple pizza, you offer me a slice of onion pizza instead–no charge for the change! If I was telling the truth about preferring onion pizza to pineapple, I should certainly accept the substitution if it’s free.

And then to round out the day, you offer me a mushroom pizza instead of the onion pizza, and again, since I prefer mushrooms to onions, I accept the swap.

I end up with exactly the same slice of mushroom pizza I started with… and one penny poorer, because I previously paid $0.01 to swap mushrooms for pineapple.

This seems like a qualitatively bad behavior on my part. By virtue of my incoherent preferences which cannot be given a consistent ordering, I have shot myself in the foot, done something self-defeating. We haven’t said how I ought to sort out my inconsistent preferences. But no matter how it shakes out, it seems like there must be some better alternative–some better way I could reason that wouldn’t spend a penny to go in circles. That is, I could at least have kept my original pizza slice and not spent the penny.

In a phrase you’re going to keep hearing, I have executed a ‘dominated strategy’: there exists some other strategy that does strictly better.

On the face of it, this seems wrong to me. Losing money for no reason is bad if you have a coherent utility function. But from the perspective of the creature actually in this situation, losing money isn’t obviously bad, or reason to change. (In a sense, the only reason you are losing money is that you consider it to be good to do so.)

It’s true that losing money is equivalent to losing pizza that you like. But losing money is also equivalent to a series of pizza improvements that you like (as just shown), so why do you want to reform based on one, while ignoring the other?

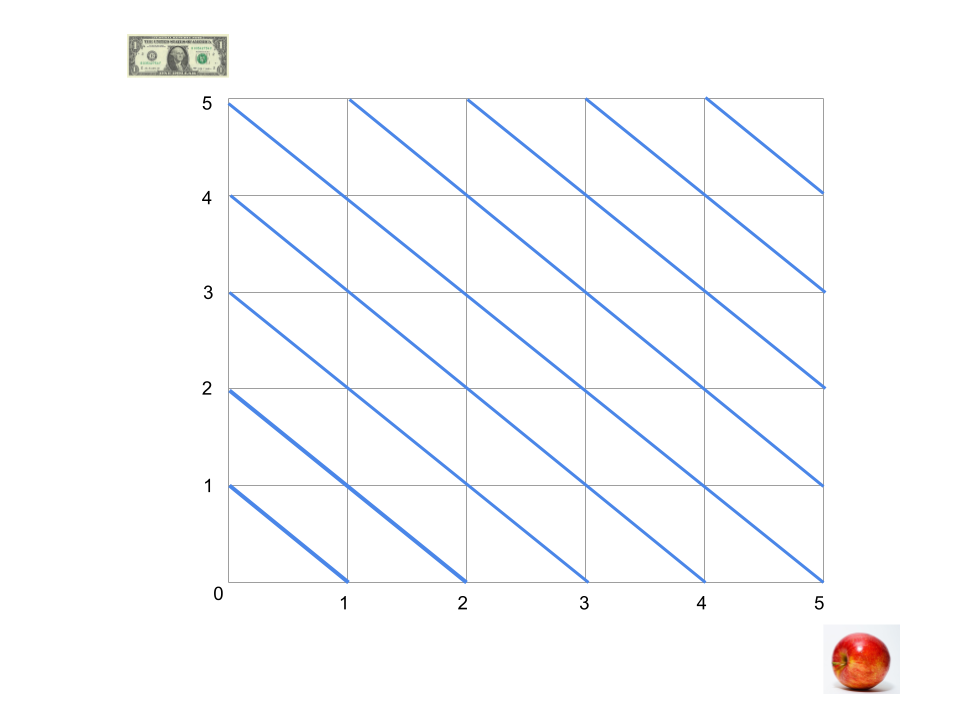

If you are even a tiny bit incoherent, then I think often a large class of things are actually implicitly worth the same amount. To see this, consider the following diagram of an entity’s preferences over money and apples. Lines are indifference curves in the space of items. The blue lines shown mean that you are indifferent between $1 and an apple on the margin across a range of financial and apple possession situations. (Not necessary for rationality.) Further out lines are better, and you can’t reach a further out line by traveling along whatever line you are on, because you are not indifferent between better and worse things.

Trades that you are fine with making can move your situation from anywhere on a line to anywhere on the same line or above it (e.g. you will trade an apple for $1 or anything more than that).

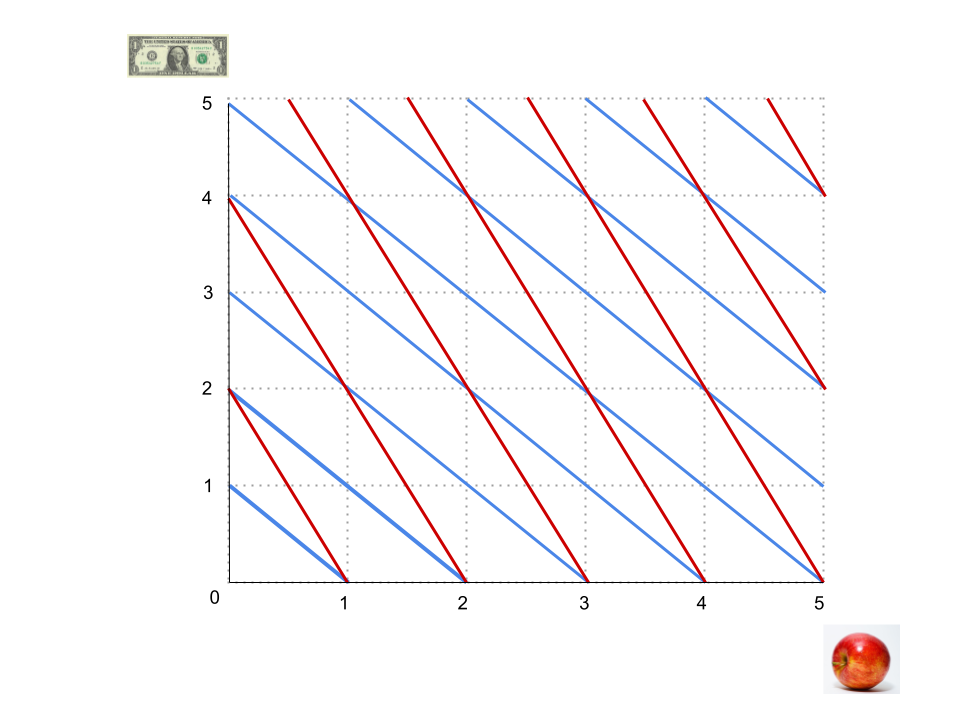

Now let’s say that you are also indifferent between an apple and $2, in general:

With two incoherent sets of preferences over the items in question, then there are two overlapping sets of curves.

If indifference curves criss-cross, then you can move anywhere among them while remaining indifferent - as long as you follow the lines, you are indifferent, and the lines now get you everywhere. Relatedly, you can get anywhere while making trades you are happy with. You are now indifferent to the whole region, at least implicitly. (In this simplest case at least, basically you now have two non-parallel vectors that you can travel along, and can add them together to get any vector in the plane.)

.png)

For instance, here, four apples are seen to be equally preferable to two apples (and also to two apples plus two dollars, and to one apple plus two dollars). Not shown because I erred: four apples are also equivalent to $-1 (which is also equivalent to winning the lottery).

If these were not lines, but higher-dimensional planes with lots of outcomes other than apples and dollars, and all of the preferences about other stuff made sense except for this one incoherence, the indifference hyperplanes would intersect and the entity in question would be effectively indifferent between everything. (To see this a different way, if it is indifferent between $1 and an apple, and also between $2 and an apple, and it considers a loaf of bread to be worth $2 in general, then implicitly a loaf of bread is worth both one apple and two apples, and so has also become caught up in the mess.)

(I don’t know if all incoherent creatures value everything the same amount - it seems like it should maybe be possible to just have a restricted region of incoherence in some cases, but I haven’t thought this through.)

This seems related to having inconsistent beliefs in logic. When once you believe a contradiction, everything follows. When once you evaluate incoherently, every evaluation follows.

And from that position of being able to evaluate anything any amount, can you say that it is better to reform your preferences to be more coherent? Yes. But you can also say that it is better to reform them to make them less coherent. Does coherence for some reason win out?

In fact slightly incoherent people don’t seem to think that they are indifferent between everything (and slightly inconsistent people don’t think they believe everything). And my impression is that people do become more coherent with time, rather than less, or a mixture at random.

If you wanted to apply this to alien AI minds though, it would seem nice to have a version of the arguments that go through, even if just via a clear account of the pragmatic considerations that compel human behavior in one direction. Does someone have an account of this? Do I misunderstand these arguments? (I haven’t actually read them for the most part, so it wouldn’t be shocking.)