Let's think about slowing down AI

(Crossposted from AI Impacts Blog)

Averting doom by not building the doom machine

If you fear that someone will build a machine that will seize control of the world and annihilate humanity, then one kind of response is to try to build further machines that will seize control of the world even earlier without destroying it, forestalling the ruinous machine’s conquest. An alternative or complementary kind of response is to try to avert such machines being built at all, at least while the degree of their apocalyptic tendencies is ambiguous.

The latter approach seems to me like the kind of basic and obvious thing worthy of at least consideration, and also in its favor, fits nicely in the genre ‘stuff that it isn’t that hard to imagine happening in the real world’. Yet my impression is that for people worried about extinction risk from artificial intelligence, strategies under the heading ‘actively slow down AI progress’ have historically been dismissed and ignored (though ‘don’t actively speed up AI progress’ is popular).

The conversation near me over the years has felt a bit like this:

Some people: AI might kill everyone. We should design a godlike super-AI of perfect goodness to prevent that.

Others: wow that sounds extremely ambitious

Some people: yeah but it’s very important and also we are extremely smart so idk it could work

[Work on it for a decade and a half]

Some people: ok that’s pretty hard, we give up

Others: oh huh shouldn’t we maybe try to stop the building of this dangerous AI?

Some people: hmm, that would involve coordinating numerous people—we may be arrogant enough to think that we might build a god-machine that can take over the world and remake it as a paradise, but we aren’t delusional

This seems like an error to me. (And lately, to a bunch of other people.)

I don’t have a strong view on whether anything in the space of ‘try to slow down some AI research’ should be done. But I think a) the naive first-pass guess should be a strong ‘probably’, and b) a decent amount of thinking should happen before writing off everything in this large space of interventions. Whereas customarily the tentative answer seems to be, ‘of course not’ and then the topic seems to be avoided for further thinking. (At least in my experience—the AI safety community is large, and for most things I say here, different experiences are probably had in different bits of it.)

Maybe my strongest view is that one shouldn’t apply such different standards of ambition to these different classes of intervention. Like: yes, there appear to be substantial difficulties in slowing down AI progress to good effect. But in technical alignment, mountainous challenges are met with enthusiasm for mountainous efforts. And it is very non-obvious that the scale of difficulty here is much larger than that involved in designing acceptably safe versions of machines capable of taking over the world before anyone else in the world designs dangerous versions.

I’ve been talking about this with people over the past many months, and have accumulated an abundance of reasons for not trying to slow down AI, most of which I’d like to argue about at least a bit. My impression is that arguing in real life has coincided with people moving toward my views.

Quick clarifications

First, to fend off misunderstanding—

- I take ‘slowing down dangerous AI’ to include any of:

- reducing the speed at which AI progress is made in general, e.g. as would occur if general funding for AI declined.

- shifting AI efforts from work leading more directly to risky outcomes to other work, e.g. as might occur if there was broadscale concern about very large AI models, and people and funding moved to other projects.

- Halting categories of work until strong confidence in its safety is possible, e.g. as would occur if AI researchers agreed that certain systems posed catastrophic risks and should not be developed until they did not. (This might mean a permanent end to some systems, if they were intrinsically unsafe.)

- I do think there is serious attention on some versions of these things, generally under other names. I see people thinking about ‘differential progress’ (b. above), and strategizing about coordination to slow down AI at some point in the future (e.g. at ‘deployment’). And I think a lot of consideration is given to avoiding actively speeding up AI progress. What I’m saying is missing are, a) consideration of actively working to slow down AI now, and b) shooting straightforwardly to ‘slow down AI’, rather than wincing from that and only considering examples of it that show up under another conceptualization (perhaps this is an unfair diagnosis).

- AI Safety is a big community, and I’ve only ever been seeing a one-person window into it, so maybe things are different e.g. in DC, or in different conversations in Berkeley. I’m just saying that for my corner of the world, the level of disinterest in this has been notable, and in my view misjudged.

Why not slow down AI? Why not consider it?

Ok, so if we tentatively suppose that this topic is worth even thinking about, what do we think? Is slowing down AI a good idea at all? Are there great reasons for dismissing it?

Scott Alexander wrote a post a little while back raising reasons to dislike the idea, roughly:

- Do you want to lose an arms race? If the AI safety community tries to slow things down, it will disproportionately slow down progress in the US, and then people elsewhere will go fast and get to be the ones whose competence determines whether the world is destroyed, and whose values determine the future if there is one. Similarly, if AI safety people criticize those contributing to AI progress, it will mostly discourage the most friendly and careful AI capabilities companies, and the reckless ones will get there first.

- One might contemplate ‘coordination’ to avoid such morbid races. But coordinating anything with the whole world seems wildly tricky. For instance, some countries are large, scary, and hard to talk to.

- Agitating for slower AI progress is ‘defecting’ against the AI capabilities folks, who are good friends of the AI safety community, and their friendship is strategically valuable for ensuring that safety is taken seriously in AI labs (as well as being non-instrumentally lovely! Hi AI capabilities friends!).

Other opinions I’ve heard, some of which I’ll address:

- Slowing AI progress is futile: for all your efforts you’ll probably just die a few years later

- Coordination based on convincing people that AI risk is a problem is absurdly ambitious. It’s practically impossible to convince AI professors of this, let alone any real fraction of humanity, and you’d need to convince a massive number of people.

- What are we going to do, build powerful AI never and die when the Earth is eaten by the sun?

- It’s actually better for safety if AI progress moves fast. This might be because the faster AI capabilities work happens, the smoother AI progress will be, and this is more important than the duration of the period. Or speeding up progress now might force future progress to be correspondingly slower. Or because safety work is probably better when done just before building the relevantly risky AI, in which case the best strategy might be to get as close to dangerous AI as possible and then stop and do safety work. Or if safety work is very useless ahead of time, maybe delay is fine, but there is little to gain by it.

- Specific routes to slowing down AI are not worth it. For instance, avoiding working on AI capabilities research is bad because it’s so helpful for learning on the path to working on alignment. And AI safety people working in AI capabilities can be a force for making safer choices at those companies.

- Advanced AI will help enough with other existential risks as to represent a net lowering of existential risk overall.1

- Regulators are ignorant about the nature of advanced AI (partly because it doesn’t exist, so everyone is ignorant about it). Consequently they won’t be able to regulate it effectively, and bring about desired outcomes.

My impression is that there are also less endorsable or less altruistic or more silly motives floating around for this attention allocation. Some things that have come up at least once in talking to people about this, or that seem to be going on:

- Advanced AI might bring manifold wonders, e.g. long lives of unabated thriving. Getting there a bit later is fine for posterity, but for our own generation it could mean dying as our ancestors did while on the cusp of a utopian eternity. Which would be pretty disappointing. For a person who really believes in this future, it can be tempting to shoot for the best scenario—humanity builds strong, safe AI in time to save this generation—rather than the scenario where our own lives are inevitably lost.

- Sometimes people who have a heartfelt appreciation for the flourishing that technology has afforded so far can find it painful to be superficially on the side of Luddism here.

- Figuring out how minds work well enough to create new ones out of math is an incredibly deep and interesting intellectual project, which feels right to take part in. It can be hard to intuitively feel like one shouldn’t do it.

(Illustration from a co-founder of modern computational reinforcement learning: )It will be the greatest intellectual achievement of all time.

— Richard Sutton (@RichardSSutton) September 29, 2022

An achievement of science, of engineering, and of the humanities,

whose significance is beyond humanity,

beyond life,

beyond good and bad. - It is uncomfortable to contemplate projects that would put you in conflict with other people. Advocating for slower AI feels like trying to impede someone else’s project, which feels adversarial and can feel like it has a higher burden of proof than just working on your own thing.

- ‘Slow-down-AGI’ sends people’s minds to e.g. industrial sabotage or terrorism, rather than more boring courses, such as, ‘lobby for labs developing shared norms for when to pause deployment of models’. This understandably encourages dropping the thought as soon as possible.

- My weak guess is that there’s a kind of bias at play in AI risk thinking in general, where any force that isn’t zero is taken to be arbitrarily intense. Like, if there is pressure for agents to exist, there will arbitrarily quickly be arbitrarily agentic things. If there is a feedback loop, it will be arbitrarily strong. Here, if stalling AI can’t be forever, then it’s essentially zero time. If a regulation won’t obstruct every dangerous project, then is worthless. Any finite economic disincentive for dangerous AI is nothing in the face of the omnipotent economic incentives for AI. I think this is a bad mental habit: things in the real world often come down to actual finite quantities. This is very possibly an unfair diagnosis. (I’m not going to discuss this later; this is pretty much what I have to say.)

- I sense an assumption that slowing progress on a technology would be a radical and unheard-of move.

- I agree with lc that there seems to have been a quasi-taboo on the topic, which perhaps explains a lot of the non-discussion, though still calls for its own explanation. I think it suggests that concerns about uncooperativeness play a part, and the same for thinking of slowing down AI as centrally involving antisocial strategies. </ul> </div></div>

- Huge amounts of medical research, including really important medical research e.g. The FDA banned human trials of strep A vaccines from the 70s to the 2000s, in spite of 500,000 global deaths every year. A lot of people also died while covid vaccines went through all the proper trials.

- Nuclear energy

- Fracking

- Various genetics things: genetic modification of foods, gene drives, early recombinant DNA researchers famously organized a moratorium and then ongoing research guidelines including prohibition of certain experiments (see the Asilomar Conference)

- Nuclear, biological, and maybe chemical weapons (or maybe these just aren’t useful)

- Various human reproductive innovation: cloning of humans, genetic manipulation of humans (a notable example of an economically valuable technology that is to my knowledge barely pursued across different countries, without explicit coordination between those countries, even though it would make those countries more competitive. Someone used CRISPR on babies in China, but was imprisoned for it.)

- Recreational drug development

- Geoengineering

- Much of science about humans? I recently ran this survey, and was reminded how encumbering ethical rules are for even incredibly innocuous research. As far as I could tell the EU now makes it illegal to collect data in the EU unless you promise to delete the data from anywhere that it might have gotten to if the person who gave you the data wishes for that at some point. In all, dealing with this and IRB-related things added maybe more than half of the effort of the project. Plausibly I misunderstand the rules, but I doubt other researchers are radically better at figuring them out than I am.

- There are probably examples from fields considered distasteful or embarrassing to associate with, but it’s hard as an outsider to tell which fields are genuinely hopeless versus erroneously considered so. If there are economically valuable health interventions among those considered wooish, I imagine they would be much slower to be identified and pursued by scientists with good reputations than a similarly promising technology not marred in that way. Scientific research into intelligence is more clearly slowed by stigma, but it is less clear to me what the economically valuable upshot would be.

- (I think there are many other things that could be in this list, but I don’t have time to review them at the moment. This page might collect more of them in future.)

- Don’t actively forward AI progress, e.g. by devoting your life or millions of dollars to it (this one is often considered already)

- Try to convince researchers, funders, hardware manufacturers, institutions etc that they too should stop actively forwarding AI progress

- Try to get any of those people to stop actively forwarding AI progress even if they don’t agree with you: through negotiation, payments, public reproof, or other activistic means.

- Try to get the message to the world that AI is heading toward being seriously endangering. If AI progress is broadly condemned, this will trickle into myriad decisions: job choices, lab policies, national laws. To do this, for instance produce compelling demos of risk, agitate for stigmatization of risky actions, write science fiction illustrating the problems broadly and evocatively (I think this has actually been helpful repeatedly in the past), go on TV, write opinion pieces, help organize and empower the people who are already concerned, etc.

- Help organize the researchers who think their work is potentially omnicidal into coordinated action on not doing it.

- Move AI resources from dangerous research to other research. Move investments from projects that lead to large but poorly understood capabilities, to projects that lead to understanding these things e.g. theory before scaling (see differential technological development in general5).

- Formulate specific precautions for AI researchers and labs to take in different well-defined future situations, Asilomar Conference style. These could include more intense vetting by particular parties or methods, modifying experiments, or pausing lines of inquiry entirely. Organize labs to coordinate on these.

- Reduce available compute for AI, e.g. via regulation of production and trade, seller choices, purchasing compute, trade strategy.

- At labs, choose policies that slow down other labs, e.g. reduce public helpful research outputs

- Alter the publishing system and incentives to reduce research dissemination. E.g. A journal verifies research results and releases the fact of their publication without any details, maintains records of research priority for later release, and distributes funding for participation. (This is how Szilárd and co. arranged the mitigation of 1940s nuclear research helping Germany, except I’m not sure if the compensatory funding idea was used.6)

- The above actions would be taken through choices made by scientists, or funders, or legislators, or labs, or public observers, etc. Communicate with those parties, or help them act.

- Not eating sand. The whole world coordinates to barely eat any sand at all. How do they manage it? It is actually not in almost anyone’s interest to eat sand, so the mere maintenance of sufficient epistemological health to have this widely recognized does the job.

- Eschewing bestiality: probably some people think bestiality is moral, but enough don’t that engaging in it would risk huge stigma. Thus the world coordinates fairly well on doing very little of it.

- Not wearing Victorian attire on the streets: this is similar but with no moral blame involved. Historic dress is arguably often more aesthetic than modern dress, but even people who strongly agree find it unthinkable to wear it in general, and assiduously avoid it except for when they have ‘excuses’ such as a special party. This is a very strong coordination against what appears to otherwise be a ubiquitous incentive (to be nicer to look at). As far as I can tell, it’s powered substantially by the fact that it is ‘not done’ and would now be weird to do otherwise. (Which is a very general-purpose mechanism.)

- Political correctness: public discourse has strong norms about what it is okay to say, which do not appear to derive from a vast majority of people agreeing about this (as with bestiality say). New ideas about what constitutes being politically correct sometimes spread widely. This coordinated behavior seems to be roughly due to decentralized application of social punishment, from both a core of proponents, and from people who fear punishment for not punishing others. Then maybe also from people who are concerned by non-adherence to what now appears to be the norm given the actions of the others. This differs from the above examples, because it seems like it could persist even with a very small set of people agreeing with the object-level reasons for a norm. If failing to advocate for the norm gets you publicly shamed by advocates, then you might tend to advocate for it, making the pressure stronger for everyone else.

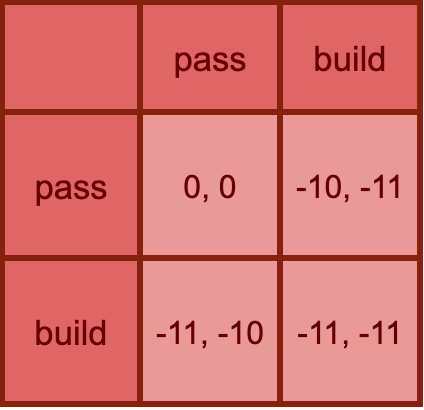

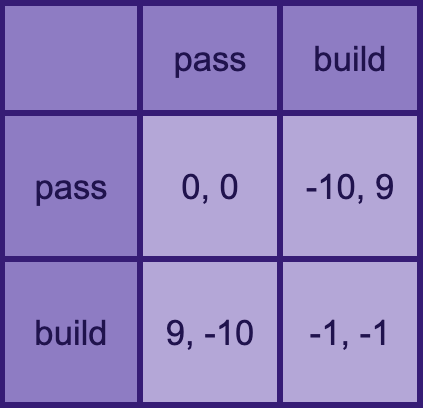

- Each player divides their effort between safety and capabilities

- One player ‘wins’, i.e. builds ‘AGI’ (artificial general intelligence) first.

- P(Alice wins) is a logistic function of Alice’s capabilities investment relative to Bob’s

- Each players’ total safety is their own safety investment plus a fraction of the other’s safety investment.

- For each player there is some distribution of outcomes if they achieve safety, and a set of outcomes if they do not, which takes into account e.g. their proclivities for enacting stupid near-term lock-ins.

- The outcome is a distribution over winners and states of alignment, each of which is a distribution of worlds (e.g. utopia, near-term good lock-in..)

- That all gives us a number of utils (Delicious utils!)

- AI is pretty safe: unaligned AGI has a mere 7% chance of causing doom, plus a further 7% chance of causing short term lock-in of something mediocre

- Your opponent risks bad lock-in: If there’s a ‘lock-in’ of something mediocre, your opponent has a 5% chance of locking in something actively terrible, whereas you’ll always pick good mediocre lock-in world (and mediocre lock-ins are either 5% as good as utopia, -5% as good)

- Your opponent risks messing up utopia: In the event of aligned AGI, you will reliably achieve the best outcome, whereas your opponent has a 5% chance of ending up in a ‘mediocre bad’ scenario then too.

- Safety investment obliterates your chance of getting to AGI first: moving from no safety at all to full safety means you go from a 50% chance of being first to a 0% chance

- Your opponent is racing: Your opponent is investing everything in capabilities and nothing in safety

- Safety work helps others at a steep discount: your safety work contributes 50% to the other player’s safety

- The researchers themselves probably don’t want to destroy the world. Many of them also actually agree that AI is a serious existential risk. So in two natural ways, pushing for caution is cooperative with many if not most AI researchers.

- AI researchers do not have a moral right to endanger the world, that someone would be stepping on by requiring that they move more cautiously. Like, why does ‘cooperation’ look like the safety people bowing to what the more reckless capabilities people want, to the point of fearing to represent their actual interests, while the capabilities people uphold their side of the ‘cooperation’ by going ahead and building dangerous AI? This situation might make sense as a natural consequence of different people’s power in the situation. But then don’t call it a ‘cooperation’, from which safety-oriented parties would be dishonorably ‘defecting’ were they to consider exercising any power they did have.

- The median surveyed ML researcher seems to think AI will destroy humanity with 5-10% chance, as I mentioned

- Often people are already intellectually convinced but haven’t integrated that into their behavior, and it isn’t hard to help them organize to act on their tentative beliefs

- As noted by Scott, a lot of AI safety people have gone into AI capabilities including running AI capabilities orgs, so those people presumably consider AI to be risky already

- I don’t remember ever having any trouble discussing AI risk with random strangers. Sometimes they are also fairly worried (e.g. a makeup artist at Sephora gave an extended rant about the dangers of advanced AI, and my driver in Santiago excitedly concurred and showed me Homo Deus open on his front seat). The form of the concerns are probably a bit different from those of the AI Safety community, but I think broadly closer to, ‘AI agents are going to kill us all’ than ‘algorithmic bias will be bad’. I can’t remember how many times I have tried this, but pre-pandemic I used to talk to Uber drivers a lot, due to having no idea how to avoid it. I explained AI risk to my therapist recently, as an aside regarding his sense that I might be catastrophizing, and I feel like it went okay, though we may need to discuss again.

- My impression is that most people haven’t even come into contact with the arguments that might bring one to agree precisely with the AI safety community. For instance, my guess is that a lot of people assume that someone actually programmed modern AI systems, and if you told them that in fact they are random connections jiggled in an gainful direction unfathomably many times, just as mysterious to their makers, they might also fear misalignment.

- Nick Bostrom, Eliezer Yudkokwsy, and other early thinkers have had decent success at convincing a bunch of other people to worry about this problem, e.g. me. And to my knowledge, without writing any compelling and accessible account of why one should do so that would take less than two hours to read.

- I arrogantly think I could write a broadly compelling and accessible case for AI risk

- Whatever kind of other AI safety research or policy work people were doing could be happening at a non-negligible rate per year. (Along with all other efforts to make the situation better—if you buy a year, that’s eight billion extra person years of time, so only a tiny bit has to be spent usefully for this to be big. If a lot of people are worried, that doesn’t seem crazy.)

- Geopolitics just changes pretty often. If you seriously think a big determiner of how badly things go is inability to coordinate with certain groups, then every year gets you non-negligible opportunities for the situation changing in a favorable way.

- Public opinion can change a lot quickly. If you can only buy one year, you might still be buying a decent shot of people coming around and granting you more years. Perhaps especially if new evidence is actively avalanching in—people changed their minds a lot in February 2020.

- Other stuff happens over time. If you can take your doom today or after a couple of years of random events happening, the latter seems non-negligibly better in general.

- Implementing what can be implemented as soon as possible probably means smoother progress, which is probably safer because a) it makes it harder for one party shoot ahead of everyone and gain power, and b) people make better choices all around if they are correct about what is going on (e.g. they don’t put trust in systems that turn out to be much more powerful than expected).

- If the main thing achieved by slowing down AI progress is more time for safety research, and safety research is more effective when carried out in the context of more advanced AI, and there is a certain amount of slowing down that can be done (e.g. because one is in fact in an arms race but has some lead over competitors), then it might better to use one’s slowing budget later.

- If there is some underlying curve of potential for progress (e.g. if money that might be spent on hardware just grows a certain amount each year), then perhaps if we push ahead now that will naturally require they be slower later, so it won’t affect the overall time to powerful AI, but will mean we spend more time in the informative pre-catastrophic-AI era.

- (More things go here I think)

- As a researcher, working on capabilities prepares you to work on safety

- You think the room where AI happens will afford good options for a person who cares about safety

- “… this isn’t primarily a social-political problem, of just getting people to listen. Even if DeepMind listened, and Anthropic knew, and they both backed off from destroying the world, that would just mean Facebook AI Research destroyed the world a year(?) later.”

- “We can’t just “decide not to build AGI” because GPUs are everywhere, and knowledge of algorithms is constantly being improved and published; 2 years after the leading actor has the capability to destroy the world, 5 other actors will have the capability to destroy the world. The given lethal challenge is to solve within a time limit, driven by the dynamic in which, over time, increasingly weak actors with a smaller and smaller fraction of total computing power, become able to build AGI and destroy the world. Powerful actors all refraining in unison from doing the suicidal thing just delays this time limit – it does not lift it, unless computer hardware and computer software progress are both brought to complete severe halts across the whole Earth. The current state of this cooperation to have every big actor refrain from doing the stupid thing, is that at present some large actors with a lot of researchers and computing power are led by people who vocally disdain all talk of AGI safety (eg Facebook AI Research). Note that needing to solve AGI alignment only within a time limit, but with unlimited safe retries for rapid experimentation on the full-powered system; or only on the first critical try, but with an unlimited time bound; would both be terrifically humanity-threatening challenges by historical standards individually.”

I’m not sure if any of this fully resolves why AI safety people haven’t thought about slowing down AI more, or whether people should try to do it. But my sense is that many of the above reasons are at least somewhat wrong, and motives somewhat misguided, so I want to argue about a lot of them in turn, including both arguments and vague motivational themes.

The mundanity of the proposal

Restraint is not radical

There seems to be a common thought that technology is a kind of inevitable path along which the world must tread, and that trying to slow down or avoid any part of it would be both futile and extreme.2

But empirically, the world doesn’t pursue every technology—it barely pursues any technologies.

Sucky technologies

For a start, there are many machines that there is no pressure to make, because they have no value. Consider a machine that sprays shit in your eyes. We can technologically do that, but probably nobody has ever built that machine.

This might seem like a stupid example, because no serious ‘technology is inevitable’ conjecture is going to claim that totally pointless technologies are inevitable. But if you are sufficiently pessimistic about AI, I think this is the right comparison: if there are kinds of AI that would cause huge net costs to their creators if created, according to our best understanding, then they are at least as useless to make as the ‘spray shit in your eyes’ machine. We might accidentally make them due to error, but there is not some deep economic force pulling us to make them. If unaligned superintelligence destroys the world with high probability when you ask it to do a thing, then this is the category it is in, and it is not strange for its designs to just rot in the scrap-heap, with the machine that sprays shit in your eyes and the machine that spreads caviar on roads.

Ok, but maybe the relevant actors are very committed to being wrong about whether unaligned superintelligence would be a great thing to deploy. Or maybe you think the situation is less immediately dire and building existentially risky AI really would be good for the people making decisions (e.g. because the costs won’t arrive for a while, and the people care a lot about a shot at scientific success relative to a chunk of the future). If the apparent economic incentives are large, are technologies unavoidable?

Extremely valuable technologies

It doesn’t look like it to me. Here are a few technologies which I’d guess have substantial economic value, where research progress or uptake appears to be drastically slower than it could be, for reasons of concern about safety or ethics3:

It seems to me that intentionally slowing down progress in technologies to give time for even probably-excessive caution is commonplace. (And this is just looking at things slowed down over caution or ethics specifically—probably there are also other reasons things get slowed down.)

Furthermore, among valuable technologies that nobody is especially trying to slow down, it seems common enough for progress to be massively slowed by relatively minor obstacles, which is further evidence for a lack of overpowering strength of the economic forces at play. For instance, Fleming first took notice of mold’s effect on bacteria in 1928, but nobody took a serious, high-effort shot at developing it as a drug until 1939.4 Furthermore, in the thousands of years preceding these events, various people noticed numerous times that mold, other fungi or plants inhibited bacterial growth, but didn’t exploit this observation even enough for it not to be considered a new discovery in the 1920s. Meanwhile, people dying of infection was quite a thing. In 1930 about 300,000 Americans died of bacterial illnesses per year (around 250/100k).

My guess is that people make real choices about technology, and they do so in the face of economic forces that are feebler than commonly thought.

Restraint is not terrorism, usually

I think people have historically imagined weird things when they think of ‘slowing down AI’. I posit that their central image is sometimes terrorism (which understandably they don’t want to think about for very long), and sometimes some sort of implausibly utopian global agreement.

Here are some other things that ‘slow down AI capabilities’ could look like (where the best positioned person to carry out each one differs, but if you are not that person, you could e.g. talk to someone who is):

Coordination is not miraculous world government, usually

The common image of coordination seems to be explicit, centralized, involving of every party in the world, and something like cooperating on a prisoners’ dilemma: incentives push every rational party toward defection at all times, yet maybe through deontological virtues or sophisticated decision theories or strong international treaties, everyone manages to not defect for enough teetering moments to find another solution.

That is a possible way coordination could be. (And I think one that shouldn’t be seen as so hopeless—the world has actually coordinated on some impressive things, e.g. nuclear non-proliferation.) But if what you want is for lots of people to coincide in doing one thing when they might have done another, then there are quite a few ways of achieving that.

Consider some other case studies of coordinated behavior:

These are all cases of very broadscale coordination of behavior, none of which involve prisoners’ dilemma type situations, or people making explicit agreements which they then have an incentive to break. They do not involve centralized organization of huge multilateral agreements. Coordinated behavior can come from everyone individually wanting to make a certain choice for correlated reasons, or from people wanting to do things that those around them are doing, or from distributed behavioral dynamics such as punishment of violations, or from collaboration in thinking about a topic.

You might think they are weird examples that aren’t very related to AI. I think, a) it’s important to remember the plethora of weird dynamics that actually arise in human group behavior and not get carried away theorizing about AI in a world drained of everything but prisoners’ dilemmas and binding commitments, and b) the above are actually all potentially relevant dynamics here.

If AI in fact poses a large existential risk within our lifetimes, such that it is net bad for any particular individual, then the situation in theory looks a lot like that in the ‘avoiding eating sand’ case. It’s an option that a rational person wouldn’t want to take if they were just alone and not facing any kind of multi-agent situation. If AI is that dangerous, then not taking this inferior option could largely come from a coordination mechanism as simple as distribution of good information. (You still need to deal with irrational people and people with unusual values.)

But even failing coordinated caution from ubiquitous insight into the situation, other models might work. For instance, if there came to be somewhat widespread concern that AI research is bad, that might substantially lessen participation in it, beyond the set of people who are concerned, via mechanisms similar to those described above. Or it might give rise to a wide crop of local regulation, enforcing whatever behavior is deemed acceptable. Such regulation need not be centrally organized across the world to serve the purpose of coordinating the world, as long as it grew up in different places similarly. Which might happen because different locales have similar interests (all rational governments should be similarly concerned about losing power to automated power-seeking systems with unverifiable goals), or because—as with individuals—there are social dynamics which support norms arising in a non-centralized way.

The arms race model and its alternatives

Ok, maybe in principle you might hope to coordinate to not do self-destructive things, but realistically, if the US tries to slow down, won’t China or Facebook or someone less cautious take over the world?

Let’s be more careful about the game we are playing, game-theoretically speaking.

The arms race

What is an arms race, game theoretically? It’s an iterated prisoners’ dilemma, seems to me. Each round looks something like this:

In this example, building weapons costs one unit. If anyone ends the round with more weapons than anyone else, they take all of their stuff (ten units).

In a single round of the game it’s always better to build weapons than not (assuming your actions are devoid of implications about your opponent’s actions). And it’s always better to get the hell out of this game.

This is not much like what the current AI situation looks like, if you think AI poses a substantial risk of destroying the world.

The suicide race

A closer model: as above except if anyone chooses to build, everything is destroyed (everyone loses all their stuff—ten units of value—as well as one unit if they built).

This is importantly different from the classic ‘arms race’ in that pressing the ‘everyone loses now’ button isn’t an equilibrium strategy.

That is: for anyone who thinks powerful misaligned AI represents near-certain death, the existence of other possible AI builders is not any reason to ‘race’.

But few people are that pessimistic. How about a milder version where there’s a good chance that the players ‘align the AI’?

The safety-or-suicide race

Ok, let’s do a game like the last but where if anyone builds, everything is only maybe destroyed (minus ten to all), and in the case of survival, everyone returns to the original arms race fun of redistributing stuff based on who built more than whom (+10 to a builder and -10 to a non-builder if there is one of each). So if you build AI alone, and get lucky on the probabilistic apocalypse, can still win big.

Let’s take 50% as the chance of doom if any building happens. Then we have a game whose expected payoffs are half way between those in the last two games:

Now you want to do whatever the other player is doing: build if they’ll build, pass if they’ll pass.

If the odds of destroying the world were very low, this would become the original arms race, and you’d always want to build. If very high, it would become the suicide race, and you’d never want to build. What the probabilities have to be in the real world to get you into something like these different phases is going to be different, because all these parameters are made up (the downside of human extinction is not 10x the research costs of building powerful AI, for instance).

But my point stands: even in terms of simplish models, it’s very non-obvious that we are in or near an arms race. And therefore, very non-obvious that racing to build advanced AI faster is even promising at a first pass.

In less game-theoretic terms: if you don’t seem anywhere near solving alignment, then racing as hard as you can to be the one who it falls upon to have solved alignment—especially if that means having less time to do so, though I haven’t discussed that here—is probably unstrategic. Having more ideologically pro-safety AI designers win an ‘arms race’ against less concerned teams is futile if you don’t have a way for such people to implement enough safety to actually not die, which seems like a very live possibility. (Robby Bensinger and maybe Andrew Critch somewhere make similar points.)

Conversations with my friends on this kind of topic can go like this:

Me: there’s no real incentive to race if the prize is mutual death

Them: sure, but it isn’t—if there’s a sliver of hope of surviving unaligned AI, and if your side taking control in that case is a bit better in expectation, and if they are going to build powerful AI anyway, then it’s worth racing. The whole future is on the line!

Me: Wouldn’t you still be better off directing your own efforts to safety, since your safety efforts will also help everyone end up with a safe AI?

Them: It will probably only help them somewhat—you don’t know if the other side will use your safety research. But also, it’s not just that they have less safety research. Their values are probably worse, by your lights.

Me: If they succeed at alignment, are foreign values really worse than local ones? Probably any humans with vast intelligence at hand have a similar shot at creating a glorious human-ish utopia, no?

Them: No, even if you’re right that being similarly human gets you to similar values in the end, the other parties might be more foolish than our side, and lock-in7 some poorly thought-through version of their values that they want at the moment, or even if all projects would be so foolish, our side might have better poorly thought-through values to lock in, as well as being more likely to use safety ideas at all. Even if racing is very likely to lead to death, and survival is very likely to lead to squandering most of the value, in that sliver of happy worlds so much is at stake in whether it is us or someone else doing the squandering!

Me: Hmm, seems complicated, I’m going to need paper for this.

The complicated race/anti-race

Here is a spreadsheet of models you can make a copy of and play with.

The first model is like this:

The second model is the same except that instead of dividing effort between safety and capabilities, you choose a speed, and the amount of alignment being done by each party is an exogenous parameter.

These models probably aren’t very good, but so far support a key claim I want to make here: it’s pretty non-obvious whether one should go faster or slower in this kind of scenario—it’s sensitive to a lot of different parameters in plausible ranges.

Furthermore, I don’t think the results of quantitative analysis match people’s intuitions here.

For example, here’s a situation which I think sounds intuitively like a you-should-race world, but where in the first model above, you should actually go as slowly as possible (this should be the one plugged into the spreadsheet now):

Your best bet here (on this model) is still to maximize safety investment. Why? Because by aggressively pursuing safety, you can get the other side half way to full safety, which is worth a lot more than than the lost chance of winning. Especially since if you ‘win’, you do so without much safety, and your victory without safety is worse than your opponent’s victory with safety, even if that too is far from perfect.

So if you are in a situation in this space, and the other party is racing, it’s not obvious if it is even in your narrow interests within the game to go faster at the expense of safety, though it may be.

These models are flawed in many ways, but I think they are better than the intuitive models that support arms-racing. My guess is that the next better still models remain nuanced.

Other equilibria and other games

Even if it would be in your interests to race if the other person were racing, ‘(do nothing, do nothing)’ is often an equilibrium too in these games. At least for various settings of the parameters. It doesn’t necessarily make sense to do nothing in the hope of getting to that equilibrium if you know your opponent to be mistaken about that and racing anyway, but in conjunction with communicating with your ‘opponent’, it seems like a theoretically good strategy.

This has all been assuming the structure of the game. I think the traditional response to an arms race situation is to remember that you are in a more elaborate world with all kinds of unmodeled affordances, and try to get out of the arms race.

Being friends with risk-takers

Caution is cooperative

Another big concern is that pushing for slower AI progress is ‘defecting’ against AI researchers who are friends of the AI safety community.

For instance Steven Byrnes:

“I think that trying to slow down research towards AGI through regulation would fail, because everyone (politicians, voters, lobbyists, business, etc.) likes scientific research and technological development, it creates jobs, it cures diseases, etc. etc., and you’re saying we should have less of that. So I think the effort would fail, and also be massively counterproductive by making the community of AI researchers see the community of AGI safety / alignment people as their enemies, morons, weirdos, Luddites, whatever.”

(Also a good example of the view criticized earlier, that regulation of things that create jobs and cure diseases just doesn’t happen.)

Or Eliezer Yudkowsky, on worry that spreading fear about AI would alienate top AI labs:

I don’t think this is a natural or reasonable way to see things, because:

It could be that people in control of AI capabilities would respond negatively to AI safety people pushing for slower progress. But that should be called ‘we might get punished’ not ‘we shouldn’t defect’. ‘Defection’ has moral connotations that are not due. Calling one side pushing for their preferred outcome ‘defection’ unfairly disempowers them by wrongly setting commonsense morality against them.

At least if it is the safety side. If any of the available actions are ‘defection’ that the world in general should condemn, I claim that it is probably ‘building machines that will plausibly destroy the world, or standing by while it happens’.

(This would be more complicated if the people involved were confident that they wouldn’t destroy the world and I merely disagreed with them. But about half of surveyed researchers are actually more pessimistic than me. And in a situation where the median AI researcher thinks the field has a 5-10% chance of causing human extinction, how confident can any responsible person be in their own judgment that it is safe?)

On top of all that, I worry that highlighting the narrative that wanting more cautious progress is defection is further destructive, because it makes it more likely that AI capabilities people see AI safety people as thinking of themselves as betraying AI researchers, if anyone engages in any such efforts. Which makes the efforts more aggressive. Like, if every time you see friends, you refer to it as ‘cheating on my partner’, your partner may reasonably feel hurt by your continual desire to see friends, even though the activity itself is innocuous.

‘We’ are not the US, ‘we’ are not the AI safety community

“If ‘we’ try to slow down AI, then the other side might win.” “If ‘we’ ask for regulation, then it might harm ‘our’ relationships with AI capabilities companies.” Who are these ‘we’s? Why are people strategizing for those groups in particular?

Even if slowing AI were uncooperative, and it were important for the AI Safety community to cooperate with the AI capabilities community, couldn’t one of the many people not in the AI Safety community work on it?

I have a longstanding irritation with thoughtless talk about what ‘we’ should do, without regard for what collective one is speaking for. So I may be too sensitive about it here. But I think confusions arising from this have genuine consequences.

I think when people say ‘we’ here, they generally imagine that they are strategizing on behalf of, a) the AI safety community, b) the USA, c) themselves or d) they and their readers. But those are a small subset of people, and not even obviously the ones the speaker can most influence (does the fact that you are sitting in the US really make the US more likely to listen to your advice than e.g. Estonia? Yeah probably on average, but not infinitely much.) If these naturally identified-with groups don’t have good options, that hardly means there are no options to be had, or to be communicated to other parties. Could the speaker speak to a different ‘we’? Maybe someone in the ‘we’ the speaker has in mind knows someone not in that group? If there is a strategy for anyone in the world, and you can talk, then there is probably a strategy for you.

The starkest appearance of error along these lines to me is in writing off the slowing of AI as inherently destructive of relations between the AI safety community and other AI researchers. If we grant that such activity would be seen as a betrayal (which seems unreasonable to me, but maybe), surely it could only be a betrayal if carried out by the AI safety community. There are quite a lot of people who aren’t in the AI safety community and have a stake in this, so maybe some of them could do something. It seems like a huge oversight to give up on all slowing of AI progress because you are only considering affordances available to the AI Safety Community.

Another example: if the world were in the basic arms race situation sometimes imagined, and the United States would be willing to make laws to mitigate AI risk, but could not because China would barge ahead, then that means China is in a great place to mitigate AI risk. Unlike the US, China could propose mutual slowing down, and the US would go along. Maybe it’s not impossible to communicate this to relevant people in China.

An oddity of this kind of discussion which feels related is the persistent assumption that one’s ability to act is restricted to the United States. Maybe I fail to understand the extent to which Asia is an alien and distant land where agency doesn’t apply, but for instance I just wrote to like a thousand machine learning researchers there, and maybe a hundred wrote back, and it was a lot like interacting with people in the US.

I’m pretty ignorant about what interventions will work in any particular country, including the US, but I just think it’s weird to come to the table assuming that you can essentially only affect things in one country. Especially if the situation is that you believe you have unique knowledge about what is in the interests of people in other countries. Like, fair enough I would be deal-breaker-level pessimistic if you wanted to get an Asian government to elect you leader or something. But if you think advanced AI is highly likely to destroy the world, including other countries, then the situation is totally different. If you are right, then everyone’s incentives are basically aligned.

I more weakly suspect some related mental shortcut is misshaping the discussion of arms races in general. The thought that something is a ‘race’ seems much stickier than alternatives, even if the true incentives don’t really make it a race. Like, against the laws of game theory, people sort of expect the enemy to try to believe falsehoods, because it will better contribute to their racing. And this feels like realism. The uncertain details of billions of people one barely knows about, with all manner of interests and relationships, just really wants to form itself into an ‘us’ and a ‘them’ in zero-sum battle. This is a mental shortcut that could really kill us.

My impression is that in practice, for many of the technologies slowed down for risk or ethics, mentioned in section ‘Extremely valuable technologies’ above, countries with fairly disparate cultures have converged on similar approaches to caution. I take this as evidence that none of ethical thought, social influence, political power, or rationality are actually very siloed by country, and in general the ‘countries in contest’ model of everything isn’t very good.

Notes on tractability

Convincing people doesn’t seem that hard

When I say that ‘coordination’ can just look like popular opinion punishing an activity, or that other countries don’t have much real incentive to build machines that will kill them, I think a common objection is that convincing people of the real situation is hopeless. The picture seems to be that the argument for AI risk is extremely sophisticated and only able to be appreciated by the most elite of intellectual elites—e.g. it’s hard enough to convince professors on Twitter, so surely the masses are beyond its reach, and foreign governments too.

This doesn’t match my overall experience on various fronts.

Some observations:

My weak guess is that immovable AI risk skeptics are concentrated in intellectual circles near the AI risk people, especially on Twitter, and that people with less of a horse in the intellectual status race are more readily like, ‘oh yeah, superintelligent robots are probably bad’. It’s not clear that most people even need convincing that there is a problem, though they don’t seem to consider it the most pressing problem in the world. (Though all of this may be different in cultures I am more distant from, e.g. in China.) I’m pretty non-confident about this, but skimming survey evidence suggests there is substantial though not overwhelming public concern about AI in the US8.

Do you need to convince everyone?

I could be wrong, but I’d guess convincing the ten most relevant leaders of AI labs that this is a massive deal, worth prioritizing, actually gets you a decent slow-down. I don’t have much evidence for this.

Buying time is big

You probably aren’t going to avoid AGI forever, and maybe huge efforts will buy you a couple of years.9 Could that even be worth it?

Seems pretty plausible:

It is also not obvious to me that these are the time-scales on the table. My sense is that things which are slowed down by regulation or general societal distaste are often slowed down much more than a year or two, and Eliezer’s stories presume that the world is full of collectives either trying to destroy the world or badly mistaken about it, which is not a foregone conclusion.

Delay is probably finite by default

While some people worry that any delay would be so short as to be negligible, others seem to fear that if AI research were halted, it would never start again and we would fail to go to space or something. This sounds so wild to me that I think I’m missing too much of the reasoning to usefully counterargue.

Obstruction doesn’t need discernment

Another purported risk of trying to slow things down is that it might involve getting regulators involved, and they might be fairly ignorant about the details of futuristic AI, and so tenaciously make the wrong regulations. Relatedly, if you call on the public to worry about this, they might have inexacting worries that call for impotent solutions and distract from the real disaster.

I don’t buy it. If all you want is to slow down a broad area of activity, my guess is that ignorant regulations do just fine at that every day (usually unintentionally). In particular, my impression is that if you mess up regulating things, a usual outcome is that many things are randomly slower than hoped. If you wanted to speed a specific thing up, that’s a very different story, and might require understanding the thing in question.

The same goes for social opposition. Nobody need understand the details of how genetic engineering works for its ascendancy to be seriously impaired by people not liking it. Maybe by their lights it still isn’t optimally undermined yet, but just not liking anything in the vicinity does go a long way.

This has nothing to do with regulation or social shaming specifically. You need to understand much less about a car or a country or a conversation to mess it up than to make it run well. It is a consequence of the general rule that there are many more ways for a thing to be dysfunctional than functional: destruction is easier than creation.

Back at the object level, I tentatively expect efforts to broadly slow down things in the vicinity of AI progress to slow down AI progress on net, even if poorly aimed.

Safety from speed, clout from complicity

Maybe it’s actually better for safety to have AI go fast at present, for various reasons. Notably:

And maybe it’s worth it to work on capabilities research at present, for instance because:

These all seem plausible. But also plausibly wrong. I don’t know of a decisive analysis of any of these considerations, and am not going to do one here. My impression is that they could basically all go either way.

I am actually particularly skeptical of the final argument, because if you believe what I take to be the normal argument for AI risk—that superhuman artificial agents won’t have acceptable values, and will aggressively manifest whatever values they do have, to the sooner or later annihilation of humanity—then the sentiments of the people turning on such machines seem like a very small factor, so long as they still turn the machines on. And I suspect that ‘having a person with my values doing X’ is commonly overrated. But the world is messier than these models, and I’d still pay a lot to be in the room to try.

Moods and philosophies, heuristics and attitudes

It’s not clear what role these psychological characters should play in a rational assessment of how to act, but I think they do play a role, so I want to argue about them.

Technological choice is not luddism

Some technologies are better than others [citation not needed]. The best pro-technology visions should disproportionately involve awesome technologies and avoid shitty technologies, I claim. If you think AGI is highly likely to destroy the world, then it is the pinnacle of shittiness as a technology. Being opposed to having it into your techno-utopia is about as luddite as refusing to have radioactive toothpaste there. Colloquially, Luddites are against progress if it comes as technology.10 Even if that’s a terrible position, its wise reversal is not the endorsement of all ‘technology’, regardless of whether it comes as progress.

Non-AGI visions of near-term thriving

Perhaps slowing down AI progress means foregoing our own generation’s hope for life-changing technologies. Some people thus find it psychologically difficult to aim for less AI progress (with its real personal costs), rather than shooting for the perhaps unlikely ‘safe AGI soon’ scenario.

I’m not sure that this is a real dilemma. The narrow AI progress we have seen already—i.e. further applications of current techniques at current scales—seems plausibly able to help a lot with longevity and other medicine for instance. And to the extent AI efforts could be focused on e.g. medically relevant narrow systems over creating agentic scheming gods, it doesn’t sound crazy to imagine making more progress on anti-aging etc as a result (even before taking into account the probability that the agentic scheming god does not prioritize your physical wellbeing as hoped). Others disagree with me here.

Robust priors vs. specific galaxy-brained models

There are things that are robustly good in the world, and things that are good on highly specific inside-view models and terrible if those models are wrong. Slowing dangerous tech development seems like the former, whereas forwarding arms races for dangerous tech between world superpowers seems more like the latter.11 There is a general question of how much to trust your reasoning and risk the galaxy-brained plan.12 But whatever your take on that, I think we should all agree that the less thought you have put into it, the more you should regress to the robustly good actions. Like, if it just occurred to you to take out a large loan to buy a fancy car, you probably shouldn’t do it because most of the time it’s a poor choice. Whereas if you have been thinking about it for a month, you might be sure enough that you are in the rare situation where it will pay off.

On this particular topic, it feels like people are going with the specific galaxy-brained inside-view terrible-if-wrong model off the bat, then not thinking about it more.

Cheems mindset/can’t do attitude

Suppose you have a friend, and you say ‘let’s go to the beach’ to them. Sometimes the friend is like ‘hell yes’ and then even if you don’t have towels or a mode of transport or time or a beach, you make it happen. Other times, even if you have all of those things, and your friend nominally wants to go to the beach, they will note that they have a package coming later, and that it might be windy, and their jacket needs washing. And when you solve those problems, they will note that it’s not that long until dinner time. You might infer that in the latter case your friend just doesn’t want to go to the beach. And sometimes that is the main thing going on! But I think there are also broader differences in attitudes: sometimes people are looking for ways to make things happen, and sometimes they are looking for reasons that they can’t happen. This is sometimes called a ‘cheems attitude’, or I like to call it (more accessibly) a ‘can’t do attitude’.

My experience in talking about slowing down AI with people is that they seem to have a can’t do attitude. They don’t want it to be a reasonable course: they want to write it off.

Which both seems suboptimal, and is strange in contrast with historical attitudes to more technical problem-solving. (As highlighted in my dialogue from the start of the post.)

It seems to me that if the same degree of can’t-do attitude were applied to technical safety, there would be no AI safety community because in 2005 Eliezer would have noticed any obstacles to alignment and given up and gone home.

To quote a friend on this, what would it look like if we *actually tried*?

Conclusion

This has been a miscellany of critiques against a pile of reasons I’ve met for not thinking about slowing down AI progress. I don’t think we’ve seen much reason here to be very pessimistic about slowing down AI, let alone reason for not even thinking about it.

I could go either way on whether any interventions to slow down AI in the near term are a good idea. My tentative guess is yes, but my main point here is just that we should think about it.

A lot of opinions on this subject seem to me to be poorly thought through, in error, and to have wrongly repelled the further thought that might rectify them. I hope to have helped a bit here by examining some such considerations enough to demonstrate that there are no good grounds for immediate dismissal. There are difficulties and questions, but if the same standards for ambition were applied here as elsewhere, I think we would see answers and action.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Scott Alexander, Adam Scholl, Matthijs Maas, Joe Carlsmith, Ben Weinstein-Raun, Ronny Fernandez, Aysja Johnson, Jaan Tallinn, Rick Korzekwa, Owain Evans, Andrew Critch, Michael Vassar, Jessica Taylor, Rohin Shah, Jeffrey Heninger, Zach Stein-Perlman, Anthony Aguirre, Matthew Barnett, David Krueger, Harlan Stewart, Rafe Kennedy, Nick Beckstead, Leopold Aschenbrenner, Michaël Trazzi, Oliver Habryka, Shahar Avin, Luke Muehlhauser, Michael Nielsen, Nathan Young and quite a few others for discussion and/or encouragement.

Notes

1 I haven’t heard this in recent times, so maybe views have changed. An example of earlier times: Nick Beckstead, 2015: “One idea we sometimes hear is that it would be harmful to speed up the development of artificial intelligence because not enough work has been done to ensure that when very advanced artificial intelligence is created, it will be safe. This problem, it is argued, would be even worse if progress in the field accelerated. However, very advanced artificial intelligence could be a useful tool for overcoming other potential global catastrophic risks. If it comes sooner—and the world manages to avoid the risks that it poses directly—the world will spend less time at risk from these other factors….

I found that speeding up advanced artificial intelligence—according to my simple interpretation of these survey results—could easily result in reduced net exposure to the most extreme global catastrophic risks…”

2 This is closely related to Bostrom’s Technological completion conjecture: “If scientific and technological development efforts do not effectively cease, then all important basic capabilities that could be obtained through some possible technology will be obtained.” (Bostrom, Superintelligence, pp. 228, Chapter 14, 2014)

Bostrom illustrates this kind of position (though apparently rejects it; from Superintelligence, found here): “Suppose that a policymaker proposes to cut funding for a certain research field, out of concern for the risks or long-term consequences of some hypothetical technology that might eventually grow from its soil. She can then expect a howl of opposition from the research community. Scientists and their public advocates often say that it is futile to try to control the evolution of technology by blocking research. If some technology is feasible (the argument goes) it will be developed regardless of any particular policymaker’s scruples about speculative future risks. Indeed, the more powerful the capabilities that a line of development promises to produce, the surer we can be that somebody, somewhere, will be motivated to pursue it. Funding cuts will not stop progress or forestall its concomitant dangers.”

This kind of thing is also discussed by Dafoe and Sundaram, Maas & Beard

3 (Some inspiration from Matthijs Maas’ spreadsheet, from Paths Untaken, and from GPT-3.)

4 From a private conversation with Rick Korzekwa, who may have read https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1139110/ and an internal draft at AI Impacts, probably forthcoming.

5 More here and here. I haven’t read any of these, but it’s been a topic of discussion for a while.

6 “To aid in promoting secrecy, schemes to improve incentives were devised. One method sometimes used was for authors to send papers to journals to establish their claim to the finding but ask that publication of the papers be delayed indefinitely.26,27,28,29 Szilárd also suggested offering funding in place of credit in the short term for scientists willing to submit to secrecy and organizing limited circulation of key papers.30” – Me, previously

7 ‘Lock-in’ of values is the act of using powerful technology such as AI to ensure that specific values will stably control the future.

8 And also in Britain:

‘This paper discusses the results of a nationally representative survey of the UK population on their perceptions of AI…the most common visions of the impact of AI elicit significant anxiety. Only two of the eight narratives elicited more excitement than concern (AI making life easier, and extending life). Respondents felt they had no control over AI’s development, citing the power of corporations or government, or versions of technological determinism. Negotiating the deployment of AI will require contending with these anxieties.’

9 Or so worries Eliezer Yudkowsky—

In MIRI announces new “Death With Dignity” strategy:

In AGI Ruin: A List of Lethalities:

10 I’d guess real Luddites also thought the technological changes they faced were anti-progress, but in that case were they wrong to want to avoid them?

11 I hear this is an elaboration on this theme, but I haven’t read it.

12 Leopold Aschenbrenner partly defines ‘Burkean Longtermism’ thus: “We should be skeptical of any radical inside-view schemes to positively steer the long-run future, given the froth of uncertainty about the consequences of our actions.”