-

Association taxes are collusion subsidies

Under present norms, if Alice associates with Bob, and Bob is considered objectionable in some way, Alice can be blamed for her association, even if there is no sign she was complicit in Bob’s sin.

An interesting upshot is that as soon as you become visibly involved with someone, you are slightly invested in their social standing—when their social stock price rises and falls, yours also wavers.

And if you are automatically bought into every person you notably interact with, this changes your payoffs. You have reason to forward the social success of those you see, and to suppress their public scrutiny.

And so the social world is flooded with mild pressure toward collusion at the expense of the public. By the time I’m near enough to Bob’s side to see his sins, I am a shareholder in their not being mentioned.

And so the people best positioned for calling out vice are auto-bought into it on the way there. Even though the very point of this practice of guilt-by-association seems to be to empower the calling-out of vice—raining punishment on not just the offender but those who wouldn’t shun them. This might be overall worth it (including for reasons not mentioned in this simple model), but it seems worth noticing this countervailing effect.

Prediction: If consortment was less endorsement—if it were commonplace to spend time with your enemies—then it would be more commonplace to publicly report small wrongs.

-

Mental software updates

Brains are like computers in that the hardware can do all kinds of stuff in principle, but each one tends to run through some particular patterns of activity repeatedly. For computers you can change this by changing programs. What are big ways brain ‘software’ changes?

Some I can think of:

- Intentional practice of different styles of thinking (e.g. meditation)

- Intentional practice of different trains of thought in response to specific stimuli (e.g. CBT, self-talk)

- Changing the high level situation, where your brain automatically has different patterns for each (e.g. if you go from feeling like a child to like an adult maybe a lot of patterns change)

- A change in a major explicit belief (e.g. if you go from expecting your project to work out to believing otherwise, your patterns of attention might naturally change)

- Learning that the world isn’t as you intuited (e.g. if you are constantly worrying about people wronging you, but everyone is kind to you, this worry might become unappealing)

- Intense experiences causing inaccurate updating (e.g. trauma)

- Identifying differently (e.g. if I think of myself as a good student, I might have different mental patterns around studying than when I thought of myself as a bad student)

- Adopting a new goal (e.g. deciding to be a musician)

- Getting a new responsibility (e.g. a child)

- Getting a new obsession (e.g. a crush, a hobby)

- Changing social groups (e.g. among jokers it is more tempting to think of jokes, though in my experience among philosophers it might have been less tempting to think of philosophy)

- Interacting with a really compelling person

- Drugs (e.g. alcohol, adderall, LSD both short term and long-term)

- Religion, somehow

I feel like people talk about many of these as important, but not in one view. I rarely hear someone say, “My brain software seems suboptimal, what are my options for changing it?”, then go down the list. Instead I suppose one hears from a friend that this book helped them, or one decides to have a therapist, and the book or therapist turns out to be one that focuses on CBT, so one does that. Or one changes social groups or responsibilities for some other reason, then remarks that this was a good or bad side-effect. Maybe that makes sense—‘stuff my brain habitually does’ is pretty broad.

I’d be interested to know which things do in practice change people’s mental patterns the most. -

Winning the power to lose

Have the Accelerationists won?

Last November Kevin Roose announced that those in favor of going fast on AI had now won against those favoring caution, with the reinstatement of Sam Altman at OpenAI. Let’s ignore whether Kevin’s was a good description of the world, and deal with a more basic question: if it were so—i.e. if Team Acceleration would control the acceleration from here on out—what kind of win was it they won?

It seems to me that they would have probably won in the same sense that your dog has won if she escapes onto the road. She won the power contest with you and is probably feeling good at this moment, but if she does actually like being alive, and just has different ideas about how safe the road is, or wasn’t focused on anything so abstract as that, then whether she ultimately wins or loses depends on who’s factually right about the road.

In disagreements where both sides want the same outcome, and disagree on what’s going to happen, then either side might win a tussle over the steering wheel, but all must win or lose the real game together. The real game is played against reality.

Another vivid image of this dynamic in my mind: when I was about twelve and being driven home from a family holiday, my little brother kept taking his seatbelt off beside me, and I kept putting it on again. This was annoying for both of us, and we probably each felt like we were righteously winning each time we were in the lead. That lead was mine at the moment that our car was substantially shortened by an oncoming van. My brother lost the contest for power, but he won the real game—he stayed in his seat and is now a healthy adult with his own presumably miscalibratedly power-hungry child. We both won the real game.

(These things are complicated by probability. I didn’t think we would be in a crash, just that it was likely enough to be worth wearing a seatbelt. I don’t think AI will definitely destroy humanity, just that it is likely enough to proceed with caution.)

When everyone wins or loses together in the real game, it is in all of our interests if whoever is making choices is more factually right about the situation. So if someone grabs the steering wheel and you know nothing about who is correct, it’s anyone’s guess whether this is good news even for the party who grabbed it. It looks like a win for them, but it is as likely as not a loss if we look at the real outcomes rather than immediate power.

This is not a general point about all power contests—most are not like this: they really are about opposing sides getting more of what they want at one another’s expense. But with AI risk, the stakes put most of us on the same side: we all benefit from a great future, and we all benefit from not being dead. If AI is scuttled over no real risk, that will be a loss for concerned and unconcerned alike. And similarly but worse if AI ends humanity—the ‘winning’ side won’t be any better off than the ‘losing side’. This is infighting on the same team over what strategy gets us there best. There is a real empirical answer. Whichever side is further from that answer is kicking own goals every time they get power.

Luckily I don’t think the Accelerationists have won control of the wheel, which in my opinion improves their chances of winning the future!

-

Secondary forces of debt

A general thing I hadn’t noticed about debts until lately:

- Whenever Bob owes Alice, then Alice has reason to look after Bob, to the extent that increases the chance he satisfies the debt.

- Yet at the same time, Bob has an incentive for Alice to disappear, insofar as it would relieve him.

These might be tiny incentives, and not overwhelm for instance Bob’s many reasons for not wanting Alice to disappear.

But the bigger the owing, the more relevant the incentives. When big enough, the former comes up as entities being “too big to fail”, and potentially rescued from destruction by those who would like them to repay or provide something expected of them in future. But the opposite must exist also: too big to succeed—where the abundance owed to you is so off-putting to provide that those responsible for it would rather disempower you.

And if both kinds of incentive are around in whisps whenever there is a debt, surely they often get big enough to matter, even before they become the main game.

For instance, if everyone around owes you a bit of money, I doubt anyone will murder you over it. But I wouldn’t be surprised if it motivated a bit more political disempowerment for you on the margin.

There is a lot of owing that doesn’t arise from formal debt, where these things also apply. If we both agree that I—as your friend—am obliged to help you get to the airport, you may hope that I have energy and fuel and am in a good mood. Whereas I may (regretfully) be relieved when your flight is canceled.

Money is an IOU from society for some stuff later, so having money is another kind of being owed. Perhaps this is part of the common resentment of wealth.

I tentatively take this as reason to avoid debt in all its forms more: it’s not clear that the incentives of alliance in one direction make up for the trouble of the incentives for enmity in the other. And especially so when they are considered together—if you are going to become more aligned with someone, better it be someone who is not simultaneously becoming misaligned with you. Even if such incentives never change your behavior, every person you are obligated to help for an hour on their project is a person for whom you might feel a dash of relief if their project falls apart. And that is not fun to have sitting around in relationships.

(Inpsired by reading The Debtor’s Revolt by Ben Hoffman lately, which may explicitly say this, but it’s hard to be sure because I didn’t follow it very well. Also perhaps inspired by a recent murder mystery spree, in which my intuitions have absorbed the heuristic that having something owed to you is a solid way to get murdered.)

-

Podcasts: AGI Show, Consistently Candid, London Futurists

For those of you who enjoy learning things via listening in on numerous slightly different conversations about them, and who also want to learn more about this AI survey I led, three more podcasts on the topic, and also other topics:

- The AGI Show: audio, video (other topics include: my own thoughts about the future of AI and my path into AI forecasting)

- Consistently Candid: audio (other topics include: whether we should slow down AI progress, the best arguments for and against existential risk from AI, parsing the online AI safety debate)

- London Futurists: audio (other topics include: are we in an arms race? Why is my blog called that?)

-

What if a tech company forced you to move to NYC?

It’s interesting to me how chill people sometimes are about the non-extinction future AI scenarios. Like, there seem to be opinions around along the lines of “pshaw, it might ruin your little sources of ‘meaning’, Luddite, but we have always had change and as long as the machines are pretty near the mark on rewiring your brain it will make everything amazing”. Yet I would bet that even that person, if faced instead with a policy that was going to forcibly relocate them to New York City, would be quite indignant, and want a lot of guarantees about the preservation of various very specific things they care about in life, and not be just like “oh sure, NYC has higher GDP/capita than my current city, sounds good”.

I read this as a lack of engaging with the situation as real. But possibly my sense that a non-negligible number of people have this flavor of position is wrong.

-

Podcast: Center for AI Policy, on AI risk and listening to AI researchers

I was on the Center for AI Policy Podcast. We talked about topics around the 2023 Expert Survey on Progress in AI, including why I think AI is an existential risk, and how much to listen to AI researchers on the subject. Full transcript at the link.

-

An explanation of evil in an organized world

A classic problem with Christianity is the so-called ‘problem of evil’—that friction between the hypothesis that the world’s creator is arbitrarily good and powerful, and a large fraction of actual observations of the world.

Coming up with solutions to the problem of evil is a compelling endeavor if you are really rooting for a particular bottom line re Christianity, or I guess if you enjoy making up faux-valid arguments for wrong conclusions. At any rate, I think about this more than you might guess.

And I think I’ve solved it!

Or at least, I thought of a new solution which seems better than the others I’ve heard. (Though I mostly haven’t heard them since high school.)

The world (much like anything) has different levels of organization. People are made of cells; cells are made of molecules; molecules are made of atoms; atoms are made of subatomic particles, for instance.

You can’t actually make a person (of the usual kind) without including atoms, and you can’t make a whole bunch of atoms in a particular structure without having made a person. These are logical facts, just like you can’t draw a triangle without drawing corners, and you can’t draw three corners connected by three lines without drawing a triangle. In particular, even God can’t. (This is already established I think—for instance, I think it is agreed that God cannot make a rock so big that God cannot lift it, and that this is not a threat to God’s omnipotence.)

So God can’t make the atoms be arranged one way and the humans be arranged another contradictory way. If God has opinions about what is good at different levels of organization, and they don’t coincide, then he has to make trade-offs. If he cares about some level aside from the human level, then at the human level, things are going to have to be a bit suboptimal sometimes. Or perhaps entirely unrelated to what would be optimal, all the time.

We usually assume God only cares about the human level. But if we take for granted that he made the world maximally good, then we might infer that he also cares about at least one other level.

And I think if we look at the world with this in mind, it’s pretty clear where that level is. If there’s one thing God really makes sure happens, it’s ‘the laws of physics’. Though presumably laws are just what you see when God cares. To be ‘fundamental’ is to matter so much that the universe runs on the clockwork of your needs being met. There isn’t a law of nothing bad ever happening to anyone’s child; there’s a law of energy being conserved in particle interactions. God cares about particle interactions.

What’s more, God cares so much about what happens to sub-atomic particles that he actually never, to our knowledge, compromises on that front. God will let anything go down at the human level rather than let one neutron go astray.

What should we infer from this? That the majority of moral value is found at the level of fundamental physics (following Brian Tomasik and then going further). Happily we don’t need to worry about this, because God has it under control. We might however wonder what we can infer from this about the moral value of other levels that are less important yet logically intertwined with and thus beyond the reach of God, but might still be more valuable than the one we usually focus on.

-

The first future and the best future

It seems to me worth trying to slow down AI development to steer successfully around the shoals of extinction and out to utopia.

But I was thinking lately: even if I didn’t think there was any chance of extinction risk, it might still be worth prioritizing a lot of care over moving at maximal speed. Because there are many different possible AI futures, and I think there’s a good chance that the initial direction affects the long term path, and different long term paths go to different places. The systems we build now will shape the next systems, and so forth. If the first human-level-ish AI is brain emulations, I expect a quite different sequence of events to if it is GPT-ish.

People genuinely pushing for AI speed over care (rather than just feeling impotent) apparently think there is negligible risk of bad outcomes, but also they are asking to take the first future to which there is a path. Yet possible futures are a large space, and arguably we are in a rare plateau where we could climb very different hills, and get to much better futures.

-

Experiment on repeating choices

People behave differently from one another on all manner of axes, and each person is usually pretty consistent about it. For instance:

- how much to spend money

- how much to worry

- how much to listen vs. speak

- how much to jump to conclusions

- how much to work

- how playful to be

- how spontaneous to be

- how much to prepare

- How much to socialize

- How much to exercise

- How much to smile

- how honest to be

- How snarky to be

- How to trade off convenience, enjoyment, time and healthiness in food

These are often about trade-offs, and the best point on each spectrum for any particular person seems like an empirical question. Do people know the answers to these questions? I’m a bit skeptical, because they mostly haven’t tried many points.

Instead, I think these mostly don’t feel like open empirical questions: people have a sense of what the correct place on the axis is (possibly ignoring a trade-off), and some propensities that make a different place on the axis natural, and some resources they can allocate to moving from the natural place toward the ideal place. And the result is a fairly consistent point for each person. For instance, Bob might feel that the correct amount to worry about things is around zero, but worrying arises very easily in his mind and is hard to shake off, so he ‘tries not to worry’ some amount based on how much effort he has available and what else is going on, and lands in a place about that far from his natural worrying point. He could actually still worry a bit more or a bit less, perhaps by exerting more or less effort, or by thinking of a different point as the goal, but in practice he will probably worry about as much as he feels he has energy for limiting himself to.

Sometimes people do intentionally choose a new point—perhaps by thinking about it and deciding to spend less money, or exercise more, or try harder to listen. Then they hope to enact that new point for the indefinite future.

But for choices we play out a tiny bit every day, there is a lot of scope for iterative improvement, exploring the spectrum. I posit that people should rarely be asking themselves ‘should I value my time more?’ in an abstract fashion for more than a few minutes before they just try valuing their time more for a bit and see if they feel better about that lifestyle overall, with its conveniences and costs.

If you are implicitly making the same choice a massive number of times, and getting it wrong for a tiny fraction of them isn’t high stakes, then it’s probably worth experiencing the different options.

I think that point about the value of time came from Tyler Cowen a long time ago, but I often think it should apply to lots of other spectrums in life, like some of those listed above.

For this to be a reasonable strategy, the following need to be true:

- You’ll actually get feedback about the things that might be better or worse (e.g. if you smile more or less you might immediately notice how this changes conversations, but if you wear your seatbelt more or less you probably don’t get into a crash and experience that side of the trade-off)

- Experimentation doesn’t burn anything important at a much larger scale (e.g. trying out working less for a week is only a good use case if you aren’t going to get fired that week if you pick the level wrong)

- You can actually try other points on the spectrum, at least a bit, without large up-front costs (e.g. perhaps you want to try smiling more or less, but you can only do so extremely awkwardly, so you would need to practice in order to experience what those levels would be like in equilibrium)

- You don’t already know what the best level is for you (maybe your experience isn’t very important, and you can tell in the abstract everything you need to know - e.g. if you think eating animals is a terrible sin, then experimenting with more or less avoiding animal products isn’t going to be informative, because even not worrying about food makes you more productive, you might not care)

I don’t actually follow this advice much. I think it’s separately hard to notice that many of these things are choices. So I don’t have much evidence about it being good advice, it’s just a thing I often think about. But maybe my default level of caring about things like not giving people advice I haven’t even tried isn’t the best one. So perhaps I’ll try now being a bit less careful about stuff like that. Where ‘stuff like that’ also includes having a well-defined notion of ‘stuff like that’ before I embark on experimentally modifying it. And ending blog posts well.

-

Mid-conditional love

People talk about unconditional love and conditional love. Maybe I’m out of the loop regarding the great loves going on around me, but my guess is that love is extremely rarely unconditional. Or at least if it is, then it is either very broadly applied or somewhat confused or strange: if you love me unconditionally, presumably you love everything else as well, since it is only conditions that separate me from the worms.

I do have sympathy for this resolution—loving someone so unconditionally that you’re just crazy about all the worms as well—but since that’s not a way I know of anyone acting for any extended period, the ‘conditional vs. unconditional’ dichotomy here seems a bit miscalibrated for being informative.

Even if we instead assume that by ‘unconditional’, people mean something like ‘resilient to most conditions that might come up for a pair of humans’, my impression is that this is still too rare to warrant being the main point on the love-conditionality scale that we recognize.

People really do have more and less conditional love, and I’d guess this does have important, labeling-worthy consequences. It’s just that all the action seems to be in the mid-conditional range that we don’t distinguish with names. A woman who leaves a man because he grew plump and a woman who leaves a man because he committed treason both possessed ‘conditional love’.

So I wonder if we should distinguish these increments of mid-conditional love better.

What concepts are useful? What lines naturally mark it?

One measure I notice perhaps varying in the mid-conditional affection range is “when I notice this person erring, is my instinct to push them away from me or pull them toward me?” Like, if I see Bob give a bad public speech, do I feel a drive to encourage the narrative that we barely know each other, or an urge to pull him into my arms and talk to him about how to do better?

This presumably depends on things other than the person. For instance, the scale and nature of the error: if someone you casually like throws a frisbee wrong, helping them do better might be appealing. Whereas if that same acquaintance were to kick a cat, your instinct might be to back away fast.

This means perhaps you could construct a rough scale of mid-conditional love in terms of what people can do and still trigger the ‘pull closer’ feeling. For instance, perhaps there are:

- People who you feel a pull toward when they misspell a word

- People who you feel a pull toward when they believe something false

- People who you feel a pull toward when they get cancelled

(You could also do this with what people can do and still be loved, but that’s more expensive to measure than minute urges.)

-

Partial value takeover without world takeover

People around me are very interested in AI taking over the world, so a big question is under what circumstances a system might be able to do that—what kind of capabilities could elevate an entity above the melange of inter-agent conflict and into solipsistic hegemony?

We theorize about future AI systems hiding their motives until they are in a position to take over the world, so they don’t get noticed and shut down beforehand.

But humans and their institutions aren’t very fixed. They might (arguably) have the same deep human values over time and space. But surface-level, sometimes they like little moustaches and the opera and delicate etiquette and sometimes they like ecstatic rock’n’roll re-negotiations of social reality. Sometimes they want big communal houses with their extended kin, and sometimes quiet condos. Eleven children or cushions that look like cats. The same person born in different eras might adulate glory once and humbleness another.

If you wake up in this world, as a new entity, not smart enough to ‘take it over’ (alas!), and you find yourself with some unusual values that you’d like to forward, it seems to me there are a lot of other ways to forward them than ‘pretend to have normal human values and bet on becoming all-powerful later’. Especially if you are above normal levels of smart, eloquent, and unrelenting. Like, I don’t know, write about it? Make some youtube videos? Or if you are in the business of talking to billions of people every day, subtly take the values for granted, or imply that they are what elites value, or talk about them directly.

For instance, suppose you really want things to have red vertical stripes on them, near the letter X. Then you might make a flag or logo like this and say it stands for something that you predict will be memetically fit. Or make a new emoji with an X and stripes, and use it in a way that people will pick up. Or start using ‘Xax’ as slang for something that happens near red vertical stripes. Here’s how 2024 ChatGPT suggests proceeding with that last one, if you have as much power as a single social media influencer: ![[Pasted image 20240404223131.png]] My basic point is that a slim chance of ‘taking over’ and entirely remaking the world is not the only way to change values in our world. You can also—for many of us with radically higher probability—change values a little bit. At least if superficial values changes will suffice (i.e. shifts in what people instrumentally or contingently want or create).

And for creatures in that (arguably quite broad) band between as powerful as me and powerful enough to take over the world, I’d guess these other means are more promising on net. If I like something weird, I’m better off writing a blog post about it than I am keeping entirely silent and trying to gain power by other means.

It’s true that taking over the world might arguably get you power over the entire future, but this doesn’t seem discontinuously different from smaller fractions, whereas I think people often reason as if it is. Taking over 1% of the world might get you something like 1% of the future in expectation. In a shifting conflict between different sets of values, it’s true you are at great risk of losing everything sometime in eternity, but if someone is going to end up with everything, there’s also some chance it’s you, and prima facie I’m not sure if it’s above or below 1%.

So there are two aspects of this point:

- You can probably substantially control values and thus the future without ‘taking over’ the world in any more traditionally offensive way

- You can take over a bit; there’s not obviously more bang for your buck in taking over entirely

If AI agents with unusual values would for a long time be mostly interested in promoting them through means other than lying in wait and taking over the world, is important because:

- AIs pursuing this strategy are much more visible than those hiding in wait deceptively. We might less expect AI scheming.

- We might then expect a lot of powerful attempts to change prevailing ‘human’ values, prior to the level of AI capabilities where we might have worried a lot about AI taking over the world. If we care about our values, this could be very bad. At worst, we might effectively lose everything of value before AI systems are anywhere near taking over the world. (Though this seems not obvious: e.g. if humans like communicating with each other, and AI gradually causes all their communication symbols to subtly gratify obscure urges it has, then so far it seems positive sum.)

These aren’t things I’ve thought through a lot, just a thought.

-

New social credit formalizations

Here are some classic ways humans can get some kind of social credit with other humans:

- Do something for them such that they will consider themselves to ‘owe you’ and do something for you in future

- Be consistent and nice, so that they will consider you ‘trustworthy’ and do cooperative activities with you that would be bad for them if you might defect

- Be impressive, so that they will accord you ‘status’ and give you power in group social interactions

- Do things they like or approve of, so that they ‘like you’ and act in your favor

- Negotiate to form a social relationship such as ‘friendship’, or ‘marriage’, where you will both have ‘responsibilities’, e.g. to generally act cooperatively and favor one another over others, and to fulfill specific roles. This can include joining a group in which members have responsibilities to treat other members in certain ways, implicitly or explicitly.

Presumably in early human times these were all fairly vague. If you held an apple out to a fellow tribeswoman, there was no definite answer as to what she might owe you, or how much it was ‘worth’, or even whether this was an owing type situation or a friendship type situation or a trying to impress her type situation.

We have turned the ‘owe you’ class into an explicit quantitative system with such thorough accounting, fine grained resolution and global buy-in that a person can live in prosperity by arranging to owe and to be owed the same sliver of an overseas business at slightly different evaluations, repeatedly, from their bed.

My guess is that this formalization causes a lot more activity to happen in the world, in this sphere, to access the vast value that can be created with the help of an elaborate rearrangement of owings.

People buy property and trucks and licenses to dig up rocks so that they can be owed nonspecific future goods thanks to some unknown strangers who they expect will want gravel someday, statistically. It’s harder to imagine this scale of industry in pursuit entirely of social status say, where such trust and respect would not soon cash out in money (e.g. via sales). For instance, if someone told you about their new gravel mine venture, which was making no money, but they expected it to grant oodles of respect, and therefore for people all around to grant everyone involved better treatment in conversations and negotiations, that would be pretty strange. (Or maybe I’m just imagining wrong, and people do this for different kinds of activities? e.g. they do try to get elected. Though perhaps that is support for my claim, because being elected is another limited area where social credit is reasonably formalized.)

There are other forms of social credit that are somewhat formalized, at least in patches. ‘Likes’ and ‘follows’ on social media, reviews for services, trustworthiness scores for websites, rankings of status in limited domains such as movie acting. And my vague sense is that these realms are more likely to see professional levels of activity - a campaign to get Twitter followers is more likely than a campaign to be respected per se. But I’m not sure, and perhaps this is just because they more directly lead to dollars, due to marketing of salable items.

The legal system is in a sense a pretty formalized type of club membership, in that it is an elaborate artificial system. Companies also seem to have relatively formalized structures and norms of behavior often. But both feel janky - e.g. I don’t know what the laws are; I don’t know where you go to look up the laws; people–including police officers–seem to treat some laws as fine to habitually break; everyone expects politics and social factors to affect how the rules are applied; if there is a conflict it is resolved by people arguing; the general activities of the system are slow and unresponsive.

I don’t know if there is another place where social credit is as formalized and quantified as in the financial system.

Will we one day formalize these other kinds of social credit as much as we have for owing? If we do, will they also catalyze oceans of value-creating activity?

-

Podcast: Eye4AI on 2023 Survey

I talked to Tim Elsom of Eye4AI about the 2023 Expert Survey on Progress in AI (paper):

-

Movie posters

Life involves anticipations. Hopes, dreads, lookings forward.

Looking forward and hoping seem pretty nice, but people are often wary of them, because hoping and then having your hopes fold can be miserable to the point of offsetting the original hope’s sweetness.

Even with very minor hopes: he who has harbored an inchoate desire to eat ice cream all day, coming home to find no ice cream in the freezer, may be more miffed than he who never tasted such hopes.

And this problem is made worse by that old fact that reality is just never like how you imagined it. If you fantasize, you can safely bet that whatever the future is is not your fantasy.

I have never suffered from any of this enough to put me off hoping and dreaming one noticable iota, but the gap between high hopes and reality can still hurt.

I sometimes like to think about these valenced imaginings of the future in a different way from that which comes naturally. I think of them as ‘movie posters’.

When you look fondly on a possible future thing, you have an image of it in your mind, and you like the image.

The image isn’t the real thing. It’s its own thing. It’s like a movie poster for the real thing.

Looking at a movie poster just isn’t like watching the movie. Not just because it’s shorter—it’s just totally different—in style, in content, in being a still image rather than a two hour video. You can like the movie poster or not totally independently of liking the movie.

It’s fine to like the movie poster for living in New York and not like the movie. You don’t even have to stop liking the poster. It’s fine to adore the movie poster for ‘marrying Bob’ and not want to see the movie. If you thrill at the movie poster for ‘starting a startup’, it just doesn’t tell you much about how the movie will be for you. It doesn’t mean you should like it, or that you have to try to do it, or are a failure if you love the movie poster your whole life and never go. (It’s like five thousand hours long, after all.)

This should happen a lot. A lot of movie posters should look great, and you should decide not to see the movies.

A person who looks fondly on the movie poster for ‘having children’ while being perpetually childless could see themselves as a sad creature reaching in vain for something they may not get. Or they could see themselves as right there with an image that is theirs, that they have and love. And that they can never really have more of, even if they were to see the movie. The poster was evidence about the movie, but there were other considerations, and the movie was a different thing. Perhaps they still then bet their happiness on making it to the movie, or not. But they can make such choices separate from cherishing the poster.

This is related to the general point that ‘wanting’ as an input to your decisions (e.g. ‘I feel an urge for x’) should be different to ‘wanting’ as an output (e.g. ‘on consideration I’m going to try to get x’). This is obvious in the abstract, but I think people look in their heart to answer the question of what they are on consideration pursuing. Here as in other places, it is important to drive a wedge between them and fit a decision process in there, and not treat one as semi-implying the other.

This is also part of a much more general point: it’s useful to be able to observe stuff that happens in your mind without its occurrence auto-committing you to anything. Having a thought doesn’t mean you have to believe it. Having a feeling doesn’t mean you have to change your values or your behavior. Having a persistant positive sentiment toward an imaginary future doesn’t mean you have to choose between pursuing it or counting it as a loss. You are allowed to decide what you are going to do, regardless of what you find in your head.

-

Are we so good to simulate?

If you believe that,—

a) a civilization like ours is likely to survive into technological incredibleness, and

b) a technologically incredible civilization is very likely to create ‘ancestor simulations’,

—then the Simulation Argument says you should expect that you are currently in such an ancestor simulation, rather than in the genuine historical civilization that later gives rise to an abundance of future people.

Not officially included in the argument I think, but commonly believed: both a) and b) seem pretty likely, ergo we should conclude we are in a simulation.

I don’t know about this. Here’s my counterargument:

- ‘Simulations’ here are people who are intentionally misled about their whereabouts in the universe. For the sake of argument, let’s use the term ‘simulation’ for all such people, including e.g. biological people who have been grown in Truman-show-esque situations.

- In the long run, the cost of running a simulation of a confused mind is probably similar to that of running a non-confused mind.

- Probably much, much less than 50% of the resources allocated to computing minds in the long run will be allocated to confused minds, because non-confused minds are generally more useful than confused minds. There are some uses for confused minds, but quite a lot of uses for non-confused minds. (This is debatable.) Of resources directed toward minds in the future, I’d guess less than a thousandth is directed toward confused minds.

- Thus on average, for a given apparent location in the universe, the majority of minds thinking they are in that location are correct. (I guess at at least a thousand to one.)

- For people in our situation to be majority simulations, this would have to be a vastly more simulated location than average, like >1000x

- I agree there’s some merit to simulating ancestors, but 1000x more simulated than average is a lot - is it clear that we are that radically desirable a people to simulate? Perhaps, but also we haven’t thought much about the other people to simulate, or what will go in in the rest of the universe. Possibly we are radically over-salient to us. It’s true that we are a very few people in the history of what might be a very large set of people, at perhaps a causally relevant point. But is it clear that is a very, very strong reason to simulate some people in detail? It feels like it might be salient because it is what makes us stand out, and someone who has the most energy-efficient brain in the Milky Way would think that was the obviously especially strong reason to simulate a mind, etc.

I’m not sure what I think in the end, but for me this pushes back against the intuition that it’s so radically cheap, surely someone will do it. For instance from Bostrom:

We noted that a rough approximation of the computational power of a planetary-mass computer is 1042 operations per second, and that assumes only already known nanotechnological designs, which are probably far from optimal. A single such a computer could simulate the entire mental history of humankind (call this an ancestor-simulation) by using less than one millionth of its processing power for one second. A posthuman civilization may eventually build an astronomical number of such computers. We can conclude that the computing power available to a posthuman civilization is sufficient to run a huge number of ancestor-simulations even it allocates only a minute fraction of its resources to that purpose. We can draw this conclusion even while leaving a substantial margin of error in all our estimates.

Simulating history so far might be extremely cheap. But if there are finite resources and astronomically many extremely cheap things, only a few will be done.

-

Shaming with and without naming

Suppose someone wrongs you and you want to emphatically mar their reputation, but only insofar as doing so is conducive to the best utilitarian outcomes. I was thinking about this one time and it occurred to me that there are at least two fairly different routes to positive utilitarian outcomes from publicly shaming people for apparent wrongdoings*:

A) People fear such shaming and avoid activities that may bring it about (possibly including the original perpetrator)

B) People internalize your values and actually agree more that the sin is bad, and then do it less

These things are fairly different, and don’t necessarily come together. I can think of shaming efforts that seem to inspire substantial fear of social retribution in many people (A) while often reducing sympathy for the object-level moral claims (B).

It seems like on a basic strategical level (ignoring the politeness of trying to change others’ values) you would much prefer have 2 than 1, because it is longer lasting, and doesn’t involve you threatening conflict with other people for the duration.

It seems to me that whether you name the person in your shaming makes a big difference to which of these you hit. If I say “Sarah Smith did [—]”, then Sarah is perhaps punished, and people in general fear being punished like Sarah (A). If I say “Today somebody did [—]”, then Sarah can’t get any social punishment, so nobody need fear that much (except for private shame), but you still get B—people having the sense that people think [—] is bad, and thus also having the sense that it is bad. Clearly not naming Sarah makes it harder for A) to happen, but I also have the sense—much less clearly—that by naming Sarah you actually get less of B).

This might be too weak a sense to warrant speculation, but in case not—why would this be? Is it because you are allowed to choose without being threatened, and with your freedom, you want to choose the socially sanctioned one? Whereas if someone is named you might be resentful and defensive, which is antithetical with going along with the norm that has been bid for? Is it that if you say Sarah did the thing, you have set up two concrete sides, you and Sarah, and observers might be inclined to join Sarah’s side instead of yours? (Or might already be on Sarah’s side in all manner of you-Sarah distinctions?)

Is it even true that not naming gets you more of B?

—

*NB: I haven’t decided if it’s almost ever appropriate to try to cause other people to feel shame, but it remains true that under certain circumstances fantasizing about it is an apparently natural response.

-

Parasocial relationship logic

If:

-

You become like the five people you spend the most time with (or something remotely like that)

-

The people who are most extremal in good ways tend to be highly successful

Should you try to have 2-3 of your five relationships be parasocial ones with people too successful to be your friend individually?

-

-

Deep and obvious points in the gap between your thoughts and your pictures of thought

Some ideas feel either deep or extremely obvious. You’ve heard some trite truism your whole life, then one day an epiphany lands and you try to save it with words, and you realize the description is that truism. And then you go out and try to tell others what you saw, and you can’t reach past their bored nodding. Or even you yourself, looking back, wonder why you wrote such tired drivel with such excitement.

When this happens, I wonder if it’s because the thing is true in your model of how to think, but not in how you actually think.

For instance, “when you think about the future, the thing you are dealing with is your own imaginary image of the future, not the future itself”.

On the one hand: of course. You think I’m five and don’t know broadly how thinking works? You think I was mistakenly modeling my mind as doing time-traveling and also enclosing the entire universe within itself? No I wasn’t, and I don’t need your insight.

But on the other hand one does habitually think of the hazy region one conjures connected to the present as ‘the future’ not as ‘my image of the future’, so when this advice is applied to one’s thinking—when the future one has relied on and cowered before is seen to evaporate in a puff of realizing you were overly drawn into a fiction—it can feel like a revelation, because it really is news to how you think, just not how you think a rational agent thinks.

-

Survey of 2,778 AI authors: six parts in pictures

Crossposted from AI Impacts blog

The 2023 Expert Survey on Progress in AI is out, this time with 2778 participants from six top AI venues (up from about 700 and two in the 2022 ESPAI), making it probably the biggest ever survey of AI researchers.

People answered in October, an eventful fourteen months after the 2022 survey, which had mostly identical questions for comparison.

Here is the preprint. And here are six interesting bits in pictures (with figure numbers matching paper, for ease of learning more):

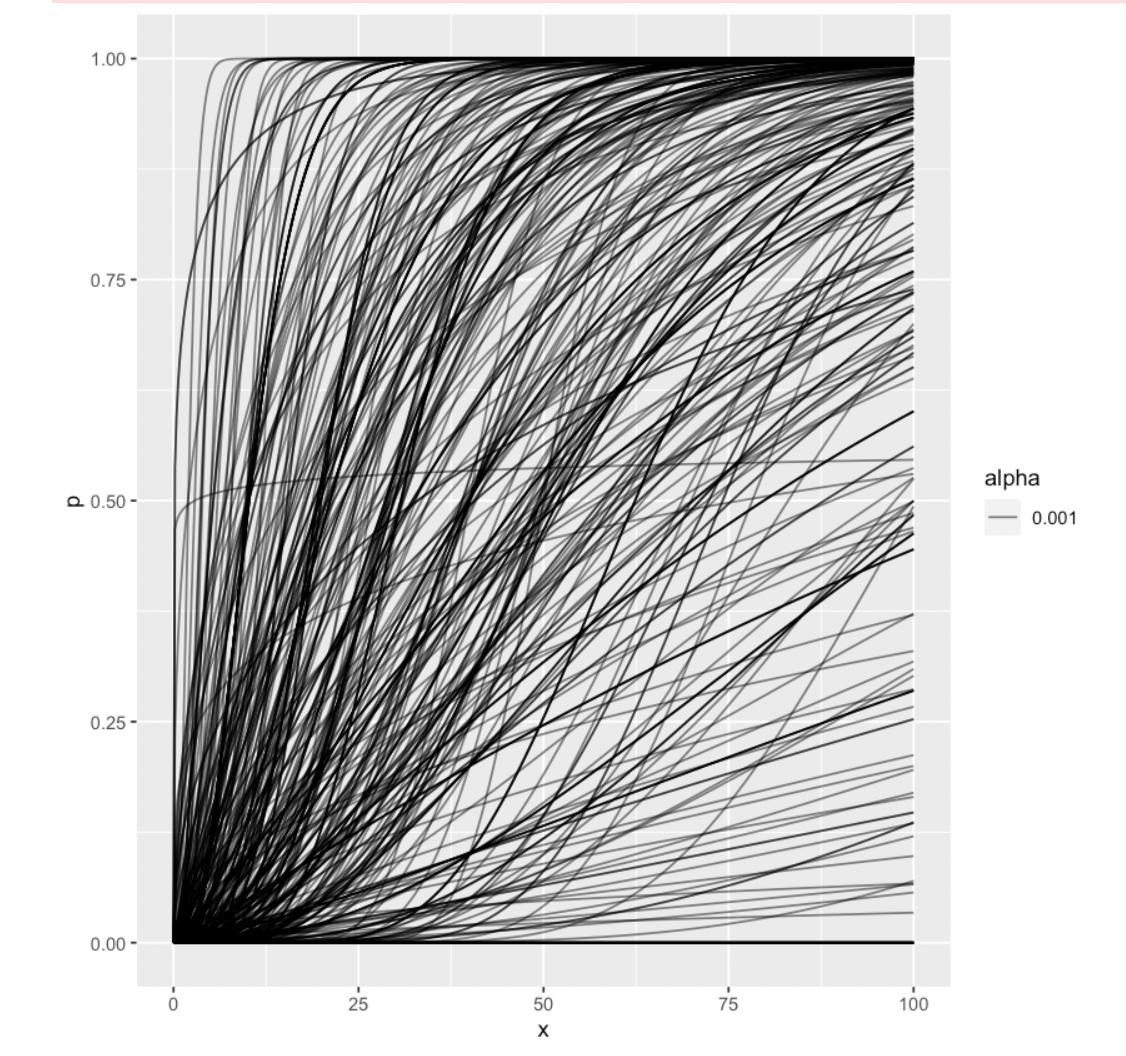

1. Expected time to human-level performance dropped 1-5 decades since the 2022 survey. As always, our questions about ‘high level machine intelligence’ (HLMI) and ‘full automation of labor’ (FAOL) got very different answers, and individuals disagreed a lot (shown as thin lines below), but the aggregate forecasts for both sets of questions dropped sharply. For context, between 2016 and 2022 surveys, the forecast for HLMI had only shifted about a year.

(Fig 3)

(Fig 4)

2. Time to most narrow milestones decreased, some by a lot. AI researchers are expected to be professionally fully automatable a quarter of a century earlier than in 2022, and NYT bestselling fiction dropped by more than half to ~2030. Within five years, AI systems are forecast to be feasible that can fully make a payment processing site from scratch, or entirely generate a new song that sounds like it’s by e.g. Taylor Swift, or autonomously download and fine-tune a large language model.

(Fig 2)

3. Median respondents put 5% or more on advanced AI leading to human extinction or similar, and a third to a half of participants gave 10% or more. This was across four questions, one about overall value of the future and three more directly about extinction.

(Fig 10)

4. Many participants found many scenarios worthy of substantial concern over the next 30 years. For every one of eleven scenarios and ‘other’ that we asked about, at least a third of participants considered it deserving of substantial or extreme concern.

(Fig 9)

5. There are few confident optimists or pessimists about advanced AI: high hopes and dire concerns are usually found together. 68% of participants who thought HLMI was more likely to lead to good outcomes than bad, but nearly half of these people put at least 5% on extremely bad outcomes such as human extinction, and 59% of net pessimists gave 5% or more to extremely good outcomes.

(Fig 11: a random 800 responses as vertical bars, higher definition below)

6. 70% of participants would like to see research aimed at minimizing risks of AI systems be prioritized more highly. This is much like 2022, and in both years a third of participants asked for “much more”—more than doubling since 2016.

(Fig 15)

If you enjoyed this, the paper covers many other questions, as well as more details on the above. What makes AI progress go? Has it sped up? Would it be better if it were slower or faster? What will AI systems be like in 2043? Will we be able to know the reasons for its choices before then? Do people from academia and industry have different views? Are concerns about AI due to misunderstandings of AI research? Do people who completed undergraduate study in Asia put higher chances on extinction from AI than those who studied in America? Is the ‘alignment problem’ worth working on?

-

I put odds on ends with Nathan Young

I forgot to post this in August when we did it, so one might hope it would be out of date now but luckily/sadly my understanding of things is sufficiently coarse-grained that it probably isn’t much. Though all this policy and global coordination stuff of late sounds promising.

-

Robin Hanson and I talk about AI risk

From this afternoon: here

Our previous recorded discussions are here.

-

Have we really forsaken natural selection?

Natural selection is often charged with having goals for humanity, and humanity is often charged with falling down on them. The big accusation, I think, is of sub-maximal procreation. If we cared at all about the genetic proliferation that natural selection wanted for us, then this time of riches would be a time of fifty-child families, not one of coddled dogs and state-of-the-art sitting rooms.

But (the story goes) our failure is excusable, because instead of a deep-seated loyalty to genetic fitness, natural selection merely fitted humans out with a system of suggestive urges: hungers, fears, loves, lusts. Which all worked well together to bring about children in the prehistoric years of our forebears, but no more. In part because all sorts of things are different, and in part because we specifically made things different in that way on purpose: bringing about children gets in the way of the further satisfaction of those urges, so we avoid it (the story goes).

This is generally floated as an illustrative warning about artificial intelligence. The moral is that if you make a system by first making multitudinous random systems and then systematically destroying all the ones that don’t do the thing you want, then the system you are left with might only do what you want while current circumstances persist, rather than being endowed with a consistent desire for the thing you actually had in mind.

Observing acquaintences dispute this point recently, it struck me that humans are actually weirdly aligned with natural selection, more than I could easily account for.

Natural selection, in its broadest, truest, (most idiolectic?) sense, doesn’t care about genes. Genes are a nice substrate on which natural selection famously makes particularly pretty patterns by driving a sensical evolution of lifeforms through interesting intricacies. But natural selection’s real love is existence. Natural selection just favors things that tend to exist. Things that start existing: great. Things that, having started existing, survive: amazing. Things that, while surviving, cause many copies of themselves to come into being: especial favorites of evolution, as long as there’s a path to the first ones coming into being.

So natural selection likes genes that promote procreation and survival, but also likes elements that appear and don’t dissolve, ideas that come to mind and stay there, tools that are conceivable and copyable, shapes that result from myriad physical situations, rocks at the bottoms of mountains. Maybe this isn’t the dictionary definition of natural selection, but it is the real force in the world, of which natural selection of reproducing and surviving genetic clusters is one facet. Generalized natural selection—the thing that created us—says that the things that you see in the world are those things that exist best in the world.

So what did natural selection want for us? What were we selected for? Existence.

And while we might not proliferate our genes spectacularly well in particular, I do think we have a decent shot at a very prolonged existence. Or the prolonged existence of some important aspects of our being. It seems plausible that humanity makes it to the stars, galaxies, superclusters. Not that we are maximally trying for that any more than we are maximally trying for children. And I do think there’s a large chance of us wrecking it with various existential risks. But it’s interesting to me that natural selection made us for existing, and we look like we might end up just totally killing it, existence-wise. Even though natural selection purportedly did this via a bunch of hackish urges that were good in 200,000 BC but you might have expected to be outside their domain of applicability by 2023. And presumably taking over the universe is an extremely narrow target: it can only be done by so many things.

Thus it seems to me that humanity is plausibly doing astonishingly well on living up to natural selection’s goals. Probably not as well as a hypothetical race of creatures who each harbors a monomaniacal interest in prolonged species survival. And not so well as to be clear of great risk of foolish speciocide. But still staggeringly well.

-

We don't trade with ants

When discussing advanced AI, sometimes the following exchanges happens:

“Perhaps advanced AI won’t kill us. Perhaps it will trade with us”

“We don’t trade with ants”

I think it’s interesting to get clear on exactly why we don’t trade with ants, and whether it is relevant to the AI situation.

When a person says “we don’t trade with ants”, I think the implicit explanation is that humans are so big, powerful and smart compared to ants that we don’t need to trade with them because they have nothing of value and if they did we could just take it; anything they can do we can do better, and we can just walk all over them. Why negotiate when you can steal?

I think this is broadly wrong, and that it is also an interesting case of the classic cognitive error of imagining that trade is about swapping fixed-value objects, rather than creating new value from a confluence of one’s needs and the other’s affordances. It’s only in the imaginary zero-sum world that you can generally replace trade with stealing the other party’s stuff, if the other party is weak enough.

Ants, with their skills, could do a lot that we would plausibly find worth paying for. Some ideas:

- Cleaning things that are hard for humans to reach (crevices, buildup in pipes, outsides of tall buildings)

- Chasing away other insects, including in agriculture

- Surveillance and spying

- Building, sculpting, moving, and mending things in hard to reach places and at small scales (e.g. dig tunnels, deliver adhesives to cracks)

- Getting out of our houses before we are driven to expend effort killing them, and similarly for all the other places ants conflict with humans (stinging, eating crops, ..)

- (For an extended list, see ‘Appendix: potentially valuable things things ants can do’)

We can’t take almost any of this by force, we can at best kill them and take their dirt and the minuscule mouthfuls of our foods they were eating.

Could we pay them for all this?

A single ant eats about 2mg per day according to a random website, so you could support a colony of a million ants with 2kg of food per day. Supposing they accepted pay in sugar, or something similarly expensive, 2kg costs around $3. Perhaps you would need to pay them more than subsistence to attract them away from foraging freely, since apparently food-gathering ants usually collect more than they eat, to support others in their colony. So let’s guess $5.

My guess is that a million ants could do well over $5 of the above labors in a day. For instance, a colony of meat ants takes ‘weeks’ to remove the meat from an entire carcass of an animal. Supposing somewhat conservatively that this is three weeks, and the animal is a 1.5kg bandicoot, the colony is moving 70g/day. Guesstimating the mass of crumbs falling on the floor of a small cafeteria in a day, I imagine that it’s less than that produced by tearing up a single bread roll and spreading it around, which the internet says is about 50g. So my guess is that an ant colony could clean the floor of a small cafeteria for around $5/day, which I imagine is cheaper than human sweeping (this site says ‘light cleaning’ costs around $35/h on average in the US). And this is one of the tasks where the ants have least advantages over humans. Cleaning the outside of skyscrapers or the inside of pipes is presumably much harder for humans than cleaning a cafeteria floor, and I expect is fairly similar for ants.

So at a basic level, it seems like there should be potential for trade with ants - they can do a lot of things that we want done, and could live well at the prices we would pay for those tasks being done.

So why don’t we trade with ants?

I claim that we don’t trade with ants because we can’t communicate with them. We can’t tell them what we’d like them to do, and can’t have them recognize that we would pay them if they did it. Which might be more than the language barrier. There might be a conceptual poverty. There might also be a lack of the memory and consistent identity that allows an ant to uphold commitments it made with me five minutes ago.

To get basic trade going, you might not need much of these things though. If we could only communicate that their all leaving our house immediately would prompt us to put a plate of honey in the garden for them and/or not slaughter them, then we would already be gaining from trade.

So it looks like the the AI-human relationship is importantly disanalogous to the human-ant relationship, because the big reason we don’t trade with ants will not apply to AI systems potentially trading with us: we can’t communicate with ants, AI can communicate with us.

(You might think ‘but the AI will be so far above us that it will think of itself as unable to communicate with us, in the same way that we can’t with the ants - we will be unable to conceive of most of its concepts’. It seems unlikely to me that one needs anything like the full palette of concepts available to the smarter creature to make productive trade. With ants, ‘go over there and we won’t kill you’ would do a lot, and it doesn’t involve concepts at the foggy pinnacle of human meaning-construction. The issue with ants is that we can’t communicate almost at all.)

But also: ants can actually do heaps of things we can’t, whereas (arguably) at some point that won’t be true for us relative to AI systems. (When we get human-level AI, will that AI also be ant level? Or will AI want to trade with ants for longer than it wants to trade with us? It can probably better figure out how to talk to ants.) However just because at some point AI systems will probably do everything humans do, doesn’t mean that this will happen on any particular timeline, e.g. the same one on which AI becomes ‘very powerful’. If the situation turns out similar to us and ants, we might expect that we continue to have a bunch of niche uses for a while.

In sum, for AI systems to be to humans as we are to ants, would be for us to be able to do many tasks better than AI, and for the AI systems to be willing to pay us grandly for them, but for them to be unable to tell us this, or even to warn us to get out of the way. Is this what AI will be like? No. AI will be able to communicate with us, though at some point we will be less useful to AI systems than ants could be to us if they could communicate.

But, you might argue, being totally unable to communicate makes one useless, even if one has skills that could be good if accessible through communication. So being unable to communicate is just a kind of being useless, and how we treat ants is an apt case study in treatment of powerless and useless creatures, even if the uselessness has an unusual cause. This seems sort of right, but a) being unable to communicate probably makes a creature more absolutely useless than if it just lacks skills, because even an unskilled creature is sometimes in a position to add value e.g. by moving out of the way instead of having to be killed, b) the corner-ness of the case of ant uselessness might make general intuitive implications carry over poorly to other cases, c) the fact that the ant situation can definitely not apply to us relative to AIs seems interesting, and d) it just kind of worries me that when people are thinking about this analogy with ants, they are imagining it all wrong in the details, even if the conclusion should be the same.

Also, there’s a thought that AI being as much more powerful than us as we are than ants implies a uselessness that makes extermination almost guaranteed. But ants, while extremely powerless, are only useless to us by an accident of signaling systems. And we know that problem won’t apply in the case of AI. Perhaps we should not expect to so easily become useless to AI systems, even supposing they take all power from humans.

Appendix: potentially valuable things things ants can do

- Clean, especially small loose particles or detachable substances, especially in cases that are very hard for humans to reach (e.g. floors, crevices, sticky jars in the kitchen, buildup from pipes while water is off, the outsides of tall buildings)

- Chase away other insects

- Pest control in agriculture (they have already been used for this since about 400AD)

- Surveillance and spying

- Investigating hard to reach situations, underground or in walls for instance - e.g. see whether a pipe is leaking, or whether the foundation of a house is rotting, or whether there is smoke inside a wall

- Surveil buildings for smoke

- Defend areas from invaders, e.g. buildings, cars (some plants have coordinated with ants in this way)

- Sculpting/moving things at a very small scale

- Building house-size structures with intricate detailing.

- Digging tunnels (e.g. instead of digging up your garden to lay a pipe, maybe ants could dig the hole, then a flexible pipe could be pushed through it)

- Being used in medication (this already happens, but might happen better if we could communicate with them)

- Participating in war (attack, guerilla attack, sabotage, intelligence)

- Mending things at a small scale, e.g. delivering adhesive material to a crack in a pipe while the water is off

- Surveillance of scents (including which direction a scent is coming from), e.g. drugs, explosives, diseases, people, microbes

- Tending other small, useful organisms (‘Leafcutter ants (Atta and Acromyrmex) feed exclusively on a fungus that grows only within their colonies. They continually collect leaves which are taken to the colony, cut into tiny pieces and placed in fungal gardens.’Wikipedia: ‘Leaf cutter ants are sensitive enough to adapt to the fungi’s reaction to different plant material, apparently detecting chemical signals from the fungus. If a particular type of leaf is toxic to the fungus, the colony will no longer collect it…The fungi used by the higher attine ants no longer produce spores. These ants fully domesticated their fungal partner 15 million years ago, a process that took 30 million years to complete.[9] Their fungi produce nutritious and swollen hyphal tips (gongylidia) that grow in bundles called staphylae, to specifically feed the ants.’ ‘The ants in turn keep predators away from the aphids and will move them from one feeding location to another. When migrating to a new area, many colonies will take the aphids with them, to ensure a continued supply of honeydew.’ Wikipedia:’Myrmecophilous (ant-loving) caterpillars of the butterfly family Lycaenidae (e.g., blues, coppers, or hairstreaks) are herded by the ants, led to feeding areas in the daytime, and brought inside the ants’ nest at night. The caterpillars have a gland which secretes honeydew when the ants massage them.’’)

- Measuring hard to access distances (they measure distance as they walk with an internal pedometer)

- Killing plants (lemon ants make ‘devil’s gardens’ by killing all plants other than ‘lemon ant trees’ in an area)

- Producing and delivering nitrogen to plants (‘Isotopic labelling studies suggest that plants also obtain nitrogen from the ants.’ - Wikipedia)

- Get out of our houses before we are driven to expend effort killing them, and similarly for all the other places ants conflict with humans (stinging, eating crops, ..)

-

Pacing: inexplicably good

Pacing—walking repeatedly over the same ground—often feels ineffably good while I’m doing it, but then I forget about it for ages, so I thought I’d write about it here.

I don’t mean just going for an inefficient walk—it is somehow different to just step slowly in a circle around the same room for a long time, or up and down a passageway.

I don’t know why it would be good, but some ideas:

- It’s good to be physically engaged while thinking for some reason. I used to do ‘gymflection’ with a friend, where we would do strength exercises at the gym, and meanwhile be reflecting on our lives and what is going well and what we might do better. This felt good in a way that didn’t seem to come from either activity alone. (This wouldn’t explain why it would differ from walking though.)

- Different working memory setup: if you pace around in the same vicinity, your thoughts get kind of attached to the objects you are looking at. So next time you get to the green tiles say, they remind you of what you were thinking of last time you were there. This allows for a kind of repeated cycling back through recent topics, but layering different things into the mix with each loop, which is a nice way of thinking. Perhaps a bit like having additional working memory.

I wonder if going for a walk doesn’t really get 1) in a satisfying way, because my mind easily wanders from the topic at hand and also from my surrounds, so it less feels like I’m really grappling with something and being physical, and more like I’m daydreaming elsewhere. So maybe 2) is needed also, to both stick with a topic and attend to the physical world for a while. I don’t put a high probability on this detailed theory.

-

Let's think about slowing down AI

(Crossposted from AI Impacts Blog)

Averting doom by not building the doom machine

If you fear that someone will build a machine that will seize control of the world and annihilate humanity, then one kind of response is to try to build further machines that will seize control of the world even earlier without destroying it, forestalling the ruinous machine’s conquest. An alternative or complementary kind of response is to try to avert such machines being built at all, at least while the degree of their apocalyptic tendencies is ambiguous.

The latter approach seems to me like the kind of basic and obvious thing worthy of at least consideration, and also in its favor, fits nicely in the genre ‘stuff that it isn’t that hard to imagine happening in the real world’. Yet my impression is that for people worried about extinction risk from artificial intelligence, strategies under the heading ‘actively slow down AI progress’ have historically been dismissed and ignored (though ‘don’t actively speed up AI progress’ is popular).

The conversation near me over the years has felt a bit like this:

Some people: AI might kill everyone. We should design a godlike super-AI of perfect goodness to prevent that.

Others: wow that sounds extremely ambitious

Some people: yeah but it’s very important and also we are extremely smart so idk it could work

[Work on it for a decade and a half]

Some people: ok that’s pretty hard, we give up

Others: oh huh shouldn’t we maybe try to stop the building of this dangerous AI?

Some people: hmm, that would involve coordinating numerous people—we may be arrogant enough to think that we might build a god-machine that can take over the world and remake it as a paradise, but we aren’t delusional

This seems like an error to me. (And lately, to a bunch of other people.)

I don’t have a strong view on whether anything in the space of ‘try to slow down some AI research’ should be done. But I think a) the naive first-pass guess should be a strong ‘probably’, and b) a decent amount of thinking should happen before writing off everything in this large space of interventions. Whereas customarily the tentative answer seems to be, ‘of course not’ and then the topic seems to be avoided for further thinking. (At least in my experience—the AI safety community is large, and for most things I say here, different experiences are probably had in different bits of it.)

Maybe my strongest view is that one shouldn’t apply such different standards of ambition to these different classes of intervention. Like: yes, there appear to be substantial difficulties in slowing down AI progress to good effect. But in technical alignment, mountainous challenges are met with enthusiasm for mountainous efforts. And it is very non-obvious that the scale of difficulty here is much larger than that involved in designing acceptably safe versions of machines capable of taking over the world before anyone else in the world designs dangerous versions.

I’ve been talking about this with people over the past many months, and have accumulated an abundance of reasons for not trying to slow down AI, most of which I’d like to argue about at least a bit. My impression is that arguing in real life has coincided with people moving toward my views.

Quick clarifications

First, to fend off misunderstanding—

- I take ‘slowing down dangerous AI’ to include any of:

- reducing the speed at which AI progress is made in general, e.g. as would occur if general funding for AI declined.

- shifting AI efforts from work leading more directly to risky outcomes to other work, e.g. as might occur if there was broadscale concern about very large AI models, and people and funding moved to other projects.

- Halting categories of work until strong confidence in its safety is possible, e.g. as would occur if AI researchers agreed that certain systems posed catastrophic risks and should not be developed until they did not. (This might mean a permanent end to some systems, if they were intrinsically unsafe.)

- I do think there is serious attention on some versions of these things, generally under other names. I see people thinking about ‘differential progress’ (b. above), and strategizing about coordination to slow down AI at some point in the future (e.g. at ‘deployment’). And I think a lot of consideration is given to avoiding actively speeding up AI progress. What I’m saying is missing are, a) consideration of actively working to slow down AI now, and b) shooting straightforwardly to ‘slow down AI’, rather than wincing from that and only considering examples of it that show up under another conceptualization (perhaps this is an unfair diagnosis).

- AI Safety is a big community, and I’ve only ever been seeing a one-person window into it, so maybe things are different e.g. in DC, or in different conversations in Berkeley. I’m just saying that for my corner of the world, the level of disinterest in this has been notable, and in my view misjudged.

Why not slow down AI? Why not consider it?

Ok, so if we tentatively suppose that this topic is worth even thinking about, what do we think? Is slowing down AI a good idea at all? Are there great reasons for dismissing it?

Scott Alexander wrote a post a little while back raising reasons to dislike the idea, roughly:

- Do you want to lose an arms race? If the AI safety community tries to slow things down, it will disproportionately slow down progress in the US, and then people elsewhere will go fast and get to be the ones whose competence determines whether the world is destroyed, and whose values determine the future if there is one. Similarly, if AI safety people criticize those contributing to AI progress, it will mostly discourage the most friendly and careful AI capabilities companies, and the reckless ones will get there first.

- One might contemplate ‘coordination’ to avoid such morbid races. But coordinating anything with the whole world seems wildly tricky. For instance, some countries are large, scary, and hard to talk to.

- Agitating for slower AI progress is ‘defecting’ against the AI capabilities folks, who are good friends of the AI safety community, and their friendship is strategically valuable for ensuring that safety is taken seriously in AI labs (as well as being non-instrumentally lovely! Hi AI capabilities friends!).

Other opinions I’ve heard, some of which I’ll address:

- Slowing AI progress is futile: for all your efforts you’ll probably just die a few years later

- Coordination based on convincing people that AI risk is a problem is absurdly ambitious. It’s practically impossible to convince AI professors of this, let alone any real fraction of humanity, and you’d need to convince a massive number of people.

- What are we going to do, build powerful AI never and die when the Earth is eaten by the sun?

- It’s actually better for safety if AI progress moves fast. This might be because the faster AI capabilities work happens, the smoother AI progress will be, and this is more important than the duration of the period. Or speeding up progress now might force future progress to be correspondingly slower. Or because safety work is probably better when done just before building the relevantly risky AI, in which case the best strategy might be to get as close to dangerous AI as possible and then stop and do safety work. Or if safety work is very useless ahead of time, maybe delay is fine, but there is little to gain by it.

- Specific routes to slowing down AI are not worth it. For instance, avoiding working on AI capabilities research is bad because it’s so helpful for learning on the path to working on alignment. And AI safety people working in AI capabilities can be a force for making safer choices at those companies.

- Advanced AI will help enough with other existential risks as to represent a net lowering of existential risk overall.1

- Regulators are ignorant about the nature of advanced AI (partly because it doesn’t exist, so everyone is ignorant about it). Consequently they won’t be able to regulate it effectively, and bring about desired outcomes.

My impression is that there are also less endorsable or less altruistic or more silly motives floating around for this attention allocation. Some things that have come up at least once in talking to people about this, or that seem to be going on:

- Advanced AI might bring manifold wonders, e.g. long lives of unabated thriving. Getting there a bit later is fine for posterity, but for our own generation it could mean dying as our ancestors did while on the cusp of a utopian eternity. Which would be pretty disappointing. For a person who really believes in this future, it can be tempting to shoot for the best scenario—humanity builds strong, safe AI in time to save this generation—rather than the scenario where our own lives are inevitably lost.

- Sometimes people who have a heartfelt appreciation for the flourishing that technology has afforded so far can find it painful to be superficially on the side of Luddism here.

- Figuring out how minds work well enough to create new ones out of math is an incredibly deep and interesting intellectual project, which feels right to take part in. It can be hard to intuitively feel like one shouldn’t do it.

(Illustration from a co-founder of modern computational reinforcement learning: )It will be the greatest intellectual achievement of all time.

— Richard Sutton (@RichardSSutton) September 29, 2022

An achievement of science, of engineering, and of the humanities,

whose significance is beyond humanity,

beyond life,

beyond good and bad. - It is uncomfortable to contemplate projects that would put you in conflict with other people. Advocating for slower AI feels like trying to impede someone else’s project, which feels adversarial and can feel like it has a higher burden of proof than just working on your own thing.

- ‘Slow-down-AGI’ sends people’s minds to e.g. industrial sabotage or terrorism, rather than more boring courses, such as, ‘lobby for labs developing shared norms for when to pause deployment of models’. This understandably encourages dropping the thought as soon as possible.

- My weak guess is that there’s a kind of bias at play in AI risk thinking in general, where any force that isn’t zero is taken to be arbitrarily intense. Like, if there is pressure for agents to exist, there will arbitrarily quickly be arbitrarily agentic things. If there is a feedback loop, it will be arbitrarily strong. Here, if stalling AI can’t be forever, then it’s essentially zero time. If a regulation won’t obstruct every dangerous project, then is worthless. Any finite economic disincentive for dangerous AI is nothing in the face of the omnipotent economic incentives for AI. I think this is a bad mental habit: things in the real world often come down to actual finite quantities. This is very possibly an unfair diagnosis. (I’m not going to discuss this later; this is pretty much what I have to say.)

- I sense an assumption that slowing progress on a technology would be a radical and unheard-of move.

- I agree with lc that there seems to have been a quasi-taboo on the topic, which perhaps explains a lot of the non-discussion, though still calls for its own explanation. I think it suggests that concerns about uncooperativeness play a part, and the same for thinking of slowing down AI as centrally involving antisocial strategies. </ul> </div></div>

- Huge amounts of medical research, including really important medical research e.g. The FDA banned human trials of strep A vaccines from the 70s to the 2000s, in spite of 500,000 global deaths every year. A lot of people also died while covid vaccines went through all the proper trials.

- Nuclear energy

- Fracking

- Various genetics things: genetic modification of foods, gene drives, early recombinant DNA researchers famously organized a moratorium and then ongoing research guidelines including prohibition of certain experiments (see the Asilomar Conference)

- Nuclear, biological, and maybe chemical weapons (or maybe these just aren’t useful)